Notes: Is Processed Food All Bad?

On building better heuristics

I was a fairly “crunchy” college student – the luxury of my tiny New York City kitchenette meant that I could usually skip out on the dining hall and the clichéd late night ramen. Instead I splurged on the good sourdough from my local bakery, cooked almost exclusively in olive oil, and made my own strawberry jam. None of this gave me joy. I don’t find cooking or grocery shopping particularly fun but I believed knowing what went in my food was important. That the unemulsified, zero-sugar peanut butter helped balance out some of the more unhealthy parts of my lifestyle.

This is important context, because I truly am sympathetic to the triad against ultra-processed food (UPF). In my dictionary, and I know the lines can get blurry here, this includes things like cheese-puffs or high-fructose candy or those little microwave meals that reach unreasonably high temperatures. More granularly you can say that I try to avoid things with palm or soybean oil and any food label where the fat content and calories consumed just do not make sense for the recommended portion size. It’s a very intuitive gray area and it would be safe to assume that we all have different operational definitions of what falls under the ultra-processed bucket.

However, we need to be careful not to over-extrapolate. Processing makes food today safe and convenient in a way that it wasn’t before. This includes practices like pasteurizing milk, which benefits everyone by removing Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria from our diet. I am aware that this is a rather low and dirty punch to make to establish my point, but there are many such cases where processing is quite obviously a net positive: salting fatty fish in airtight barrels to stop them from going rancid1, freezing vegetables at peak ripeness, or adding iodine to salt to prevent goiter.

Frustratingly, this means that the long debate on processed food requires nuance. I am not a big fan of this word because it can be used as a cop-out – transferring the burden of choice onto the individual. Yet, in this case, it seems like the best solution to the very fundamental problem of what we should be eating day in and day out is to develop better heuristics.

Methodological Constraints:

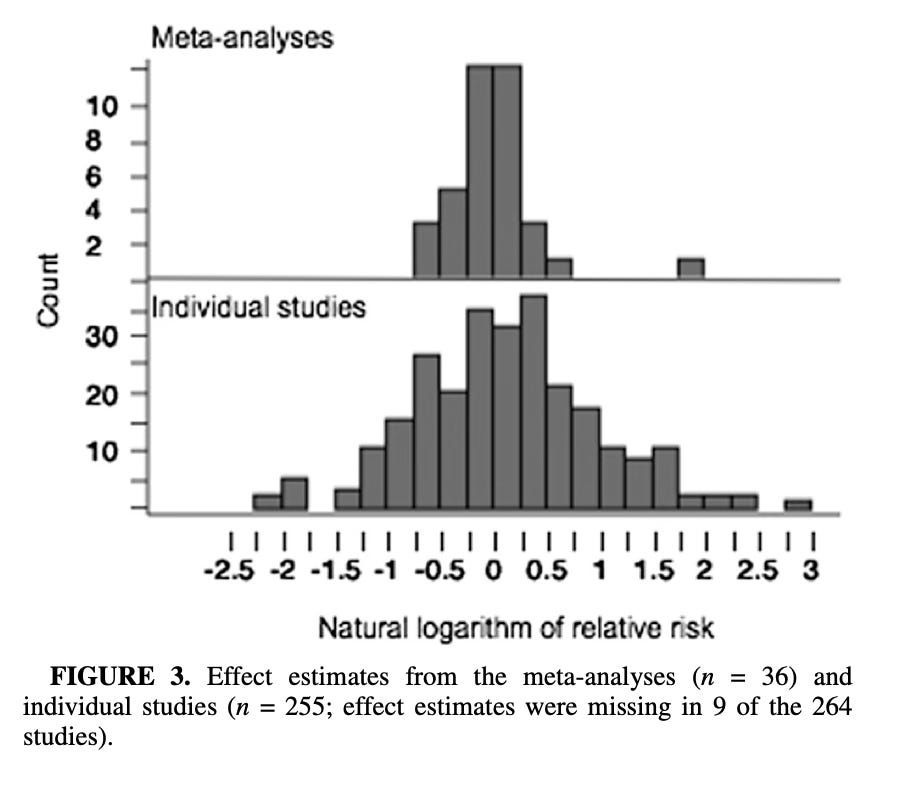

One reason inexact but well-informed intuition is important is that nutritional science studies can be unusually murky. Take, for example, this overview from 2013 that looked at 50 common ingredients and found that: “Associations with cancer risk or benefits have been claimed for most food ingredients. Many single studies highlight implausibly large effects, even though evidence is weak. Effect sizes shrink in meta-analyses.”

There are many dimensions to why this confusion occurs. For one, research on UPFs suffers from a definition problem. How can instant noodles, chicken nuggets, cookies, and fortified breakfast cereal be lumped into the same homogenized group? There is no shared mechanism that makes all of these things harmful and no consistent marker we can measure. In one recent NIH study, researchers very clearly showed this problem: “The UPFs that were associated with the highest risk for heart disease included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats such as hot dogs and deli meat. UPFs associated with the lowest risk of heart disease included breakfast cereals, yogurt, and some whole grain products. Examples of additives commonly used in UPFs include high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, sodium nitrite, and artificial dyes.” Which is to say that ultra-processed food is a broad category, and there are a lot of variables that are difficult to untangle from each other.2

Even if we could agree on what counts as a UPF, we can’t actually run a true Randomized Control Trial – we can’t assign people to only eat certain foods for years on end, nor can we constantly monitor everything people consume. This inability to control a variety of confounds and a generally high reliance on surveys (where “participants unreliably recall what they eat”) makes the problem worse.

Despite these issues, (anecdotally) it was not unusual to see methodologically limited nutrition studies being presented as fact in third-party publications3 – adding to the general fear-mongering that surrounds food. But recognizing that epistemic standards in nutrition science are shaky actually helps us navigate the noise because it means we should be skeptical of both the latest superfood craze and the newest dietary demon.

Drawing the Line:

To think through what this instinct for food should look like I will be using the words processed and ultra-processed a lot. However, there are lots of different ways to slice up the food pyramid and start labeling products good or bad. I want to avoid doing so here and also maintain some consistency when talking about processing so I am going to figuratively poke the bear and quickly explain what processed vs ultra-processed is going to mean in the context of this essay.

If we were to go by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, processed includes “any raw agricultural commodity subjected to washing, cleaning, milling, cutting, chopping, heating, pasteurizing, blanching, cooking, canning, freezing, drying, dehydrating, mixing, packaging, or other procedures that alter the food from its natural state.” This is certainly not a workable definition for the purposes of this article (I don’t think waxed apples or baby-carrots fall under our functional understanding of processed) but I have included it here just to demonstrate how large the Overton window can be.

More specifically, for ease I will be using the standard NOVA classification system: (taken verbatim from source)

Category 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods — such as whole foods, vegetables, fruit, meat and pasta. These foods may have been washed, dried, frozen or vacuum-packed but have no added ingredients.

Category 2: Culinary ingredients that have been processed, including oil, butter, sugar or salt. They are typically used only in cooking and not eaten on their own.

Category 3: Processed foods — made by combining Category 1 and 2 foods through preservation or cooking. Examples include canned tuna, fruits in syrup and salted nuts.

Category 4: Ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations made from food components. They include additives that are rare or nonexistent in culinary use, like emulsifiers, hydrogenated oils, synthetic colors, texture improvers or flavor enhancers. Think chips, soda, instant soup, pastries and mass-produced breads.

My hunch here is that most (but not all) of the foods in Category 4 are giving the word “processed” a bad rap, so much so that we are over-correcting in ways that can only be defined as romanticization of the culinary-past. This should not put us off the evidently safe, nutritious, time-saving items in categories 2 and 3 – think fortified flour, frozen veg, canned beans, or a little mono-sodium glutamate (MSG).

Two small notes, however:

1) I am going to disregard the meat industry for the most part. This is mostly because I grew up vegetarian and frankly have little stake in finding merits for the likes of animal feed that increases hot carcass weight (although if someone has written something good about this, please send it my way).4

2) I also won’t be making any socio-economic claims. One common argument for processed food is that it provides the required calories in a cheap and convenient manner.5 But this should be secondary to whether this food is actually damaging. Ease is good if, on balance, processed food itself is good for us – it cannot be an independent factor in how we set the standards for what we should be consuming.

Some Big Questions:

First let’s talk about safety because, processed or not, the top priority has to be consuming food that doesn’t actively cause harm. This brings up a few popular debates, including those on raw milk, seed oils, and food dyes. Since dairy, fat, and colouring are so ubiquitous in our food, there have been reasonable attempts to separate the signal from the noise. To establish some groundwork and context here, I am just going to summarize the clearest takes on this that I have come across.

Raw milk is very bad for us. There are no additional gut microbiome benefits or additional protein and healthy fats that get lost in the pasteurization process. Drinking milk that was once boiled is not what is causing lactose intolerance either – the heat is not destroying any imaginary lactase. I don’t believe that there are many people that fall in the raw milk camp but again it is a very good example of a widespread product that is markedly improved by processing.

Here on out, things get murkier. For example, with seed oils, it seems like a big reason behind vilifying them is a result of their inextricable tie and excessive presence in a diet where we are deriving an increasing amount of our calories from ultra-processed foods. High-fat consumption can be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular function. Similarly, increasing the amount of seed oil-derived linoleic acid or skewing the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio can also cause some downstream effects (although it is hard to definitively point out in which direction).

Dynomight has written an excellent overview on this problem and comes to the following conclusion:

“A weak version of seed oil theory is that seed oils are highly processed, so why not use cold-pressed olive oil instead? If that’s the theory, fine. In fact, this is mostly what I do myself. I figure it might be useless, but it’s unlikely to be harmful, and olive oil is delicious. And I wouldn’t be shocked if one of the suggested mechanisms for seed oil turns out to be valid. I wouldn’t be surprised at all if some mechanism turned out to be part of a larger, more complicated story. And in practice, avoiding seed oils is probably really good for you, because it forces you to eliminate most of the processed crap you shouldn’t be eating anyway.”6

I particularly like this stance because it gets to the core of the issue: UPFs are very calorically dense. It may very well be that seed-oils themselves are bad but the real confound here is that they are found in high quantities in food that just cannot leave you satiated in amounts where the macro-nutrient make-up is reasonable. It could also be plausible that if we found a cost-efficient way to make UPFs with tallow, butter, or olive oil then they would probably still be bad for us simply because of how calorically dense they are.

Fat, sugar, and calories are easy to measure and watch – but what do you do about food dyes? Recent debates spearheaded through the MAHA agenda (page 8 here) antagonize basically all synthetic colouring but testing whether this is true leads to the same problem of confounds as with seed-oils. From Colleen Smith: “There’s plenty of research on UPFs, but much of it is of mixed quality. Because UPFs bundle sugar, sweeteners, preservatives, flavors, and colorings, diet studies are confounded; therefore, UPF findings don’t automatically implicate synthetic food dyes.”

Here we might be tempted to take the same measure of precaution and switch to natural dyes but these have much looser regulations as compared to the seven legally-allowed synthetic dyes. From the same article: “Natural dyes require FDA approval to prevent inadvertent use of something poisonous. However, once approved, they are exempt from specific labeling and the monitoring inherent in batch testing…Because oversight for natural dyes is less stringent, we are at the mercy of the food industry to provide transparency on its quality control, processing, and sourcing of natural dyes. Without this transparency, a shift to these products could easily repeat the supplement industry’s problems in the 1990s, when purity and safety were far from guaranteed. Consumers shouldn’t have to worry about ending up with heavy metals, pesticides, or brick powder in their food.”

In reading the work that I have summarized here, it is clear that we should consider cutting out at-least some UPF’s. Those that fall into the quite obviously bad category include foods where high fat percentages and sugar content is crammed into teensy little “recommended” portion sizes [seriously though, try eating Nutella on toast and really stick to the 2 tbsp limit, it will be miserable breakfast despite the 21g of sugar 11g of fat]. But rationing your M&Ms should be an individual decision.

Good Ultra-Processing:

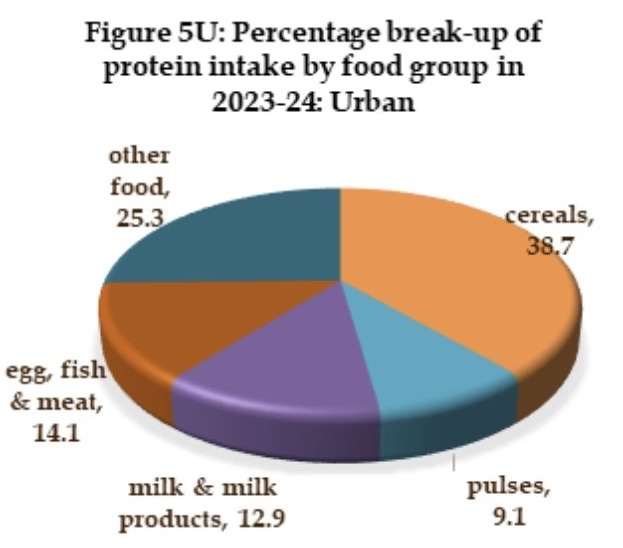

One place where ultra-processed food is clearly a net good is when it comes to protein. As I mentioned earlier in the piece, I grew up vegetarian which in and of itself is not surprising. What may be of note is that the Indian state where I was raised is 60% vegetarian. However, I don’t even fall into this massive majority because I eat eggs (which are considered non-vegetarian here). In this context, it is believable that (at least) 27 percent of households consume inadequate amounts of protein. Now this is one of the places where survey results just do not match up to observational evidence and I am not certain that the average urban-dwelling Indian consumes 63.4g of protein per day (as reported). It would be incredibly difficult to do so when a cup of milk has 4-6g and a roti (flatbread) has 2-3g. A growing number of people recognize this and the market has responded with high-protein breads, bars, powders, and yogurts.

These supplements include NOVA category 2 and 3 products such as milk and yogurt where the dairy is recomposed and modified in various ways to have a lower fat percentage and much higher protein content. More importantly, it also includes NOVA category 4 foods such as whey isolates, certain cheeses, and nut butters which are all quite necessary. For many individuals grass-fed steak and butter is just not a viable way of fulfilling their dietary needs – instead, tofu, seitan, paneer, and soy-flour enriched complex carbohydrates are all objectively good inventions that let people hit macronutrient goals while maintaining plant-based diets.

Rejecting Food Romanticism:

Yet there is a growing trend to RETVRN to the good old days – a nostalgic push on the internet with the rise of the “trad-wife” archetype, in restaurants with a steady push correlating expensive with local and organic, and in policy with curbing consumer choice. Together, they transform food choices into moral categories where choosing canned beans over dried ones is a character failing rather than a perfectly rational decision.

The fact of the matter is that most foods we consider “real” are themselves products of centuries of human intervention: selection, breeding, and cultivation techniques that would be unrecognizable to our ancestors. The bananas we eat bear little resemblance to their wild predecessor and the wheat in my feel-good sourdough has been modified through millennia of agricultural practice. Processing, in its various forms, is simply the continuation of humanity’s long project of making food safer, more nutritious, and more accessible.

“The food abundance Americans enjoyed is not because we cooperated with nature. Our abundance is a triumph of human ingenuity over nature’s indifference to us. A potential danger embedded in the worldview of the popular alternative is romanticism with nature and the past. Modern, technologically advanced food is rejected in favor of older, slower, more “natural” food. This mindset is potentially destructive because how we view our future affects not only who we are but what we become.”7

Moreover, the tools that make modern food possible – pasteurization, canning, milling, fortification, cold chains, emulsification, stabilizers – were invented to solve concrete problems: pathogens, spoilage, scarcity, cost, labor, and time. If we start from the lens of these very real issues instead of ‘vibes’, the case for a lot of processing is rather straightforward. It makes food safer, more consistent, cheaper per calorie, and easier to store and transport. It also shifts invisible burdens. Shelf stability lowers household waste. Standardization reduces batch-to-batch risk. Ready-to-use staples compress the time tax that otherwise falls on the people who cook most meals: “In 1965 American women spent an average of 113 minutes per day (almost two hours) in meal preparation. By 2007 they were spending only 66 minutes per day, a 47 percent reduction…While we might have a tendency to romanticize the past, the reality is that cooking was often a monotonous, arduous, thankless task required to keep the family fed.”8

Clearly processed food has its place and to understand what that is, (in lieu of sound, consistent research) we need better heuristics for navigating the modern culinary landscape. I propose that if we accept calories-in/calories-out as a fundamental truth then our intuitive guidelines become straightforward: be suspicious of foods where the recommended portion size seems divorced from satiation or where the macro breakdown doesn’t make sense. At the same time, there is no need to conflate these legitimate concerns with the broader project of food technology. The same processes of human ingenuity that has given us chocolate, cheese, and delicious San Marzano tomatoes year-round.

With thanks to Mike Riggs, Abby ShalekBriski, Adam Kroetsch, Ariel Patton, Colleen Smith, Dhruv Arora, and Nehal Udyavar for their suggestions and feedback on drafts.

Cover Image: Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Still Life with Monkey, Fruits, and Flowers (1724), Art Institute of Chicago.

From Lynn Townsend White Jr., Medieval Technology and Social Change, pages 75-79 + accompanying footnotes on pages 158-160.

To better understand what makes for a good scientific study from a regulatory point of view, I recommend the FDA’s Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims [on Adam Kroetsch’s suggestion].

I particularly like this article from 1981, where the New York Times perfectly illustrated the nutritional studies conundrum while covering a study that correlated coffee drinking with pancreatic cancer: “Over the years coffee drinking has been blamed for many health problems, including ulcers, high blood pressure, heart attacks, gout, birth defects, anxiety and cancers of the stomach and urinary tract, but the evidence has been questionable. In an editorial about a month ago The Lancet, another respected medical journal, said there was no convincing evidence that coffee drinking did any harm other than create the anxieties induced in some heavy users. The results of the Harvard research had not yet become known.”

However, I did appreciate this take on reducing unnecessary animal suffering.

Also see: Dynomight on processed food

Jayson L. Lusk, The Food Police [short by important read, on Abby ShalekBriski’s suggestion].

Jayson L. Lusk, Unnaturally Delicious: How Science and Technology are Serving Up Super Food to Save the World, chapter 3.

Ending with Jayson’s quote about the reduction in food preparation time is a form of socioeconomic commentary. But what a lovely way to end. Bravo, Hiya! You really did the topic justice.