Why Is Tuberculosis So Hard to Eradicate?

On the uphill battle against the world’s deadliest infection

Growing up, everyone I knew had an inconspicuous spot of discoloration on their left shoulder – an imprint of the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine which offers young children some protection against severe forms of Tuberculosis (TB).1 Later, when I moved to the United States, I learnt that this patch had a name when a friend pointed at my arm and exclaimed that she, too, had the “immigrant mark.” I had never thought of it before, but it's true – the vaccine is only mandatory in the global south, in countries where TB still poses a significant threat. Today, about 95% of the 10.8 million cases and almost 97% of all TB-related deaths occur outside of Europe and the Americas.2

This was not always the case. For example, “between 1848 and 1872 tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in Britain, accounting for 15.0 per cent of all deaths.” Similarly, the microbiologist who first identified the causative agent of TB, Robert Koch, said in his 1882 lecture that

“If the importance of a disease for mankind is measured from the number of fatalities which are due to it, then tuberculosis must be considered much more important than those most feared infectious diseases, plague, cholera, and the like. Statistics have shown that 1/7 of all humans die of tuberculosis.” 3

More recent estimates state that globally, “the annual risk of infection at the beginning of the twentieth century was so large [...in the order of magnitude of 10 or more per cent] that it was very unlikely that a person could escape infection by the time of reaching adulthood.”

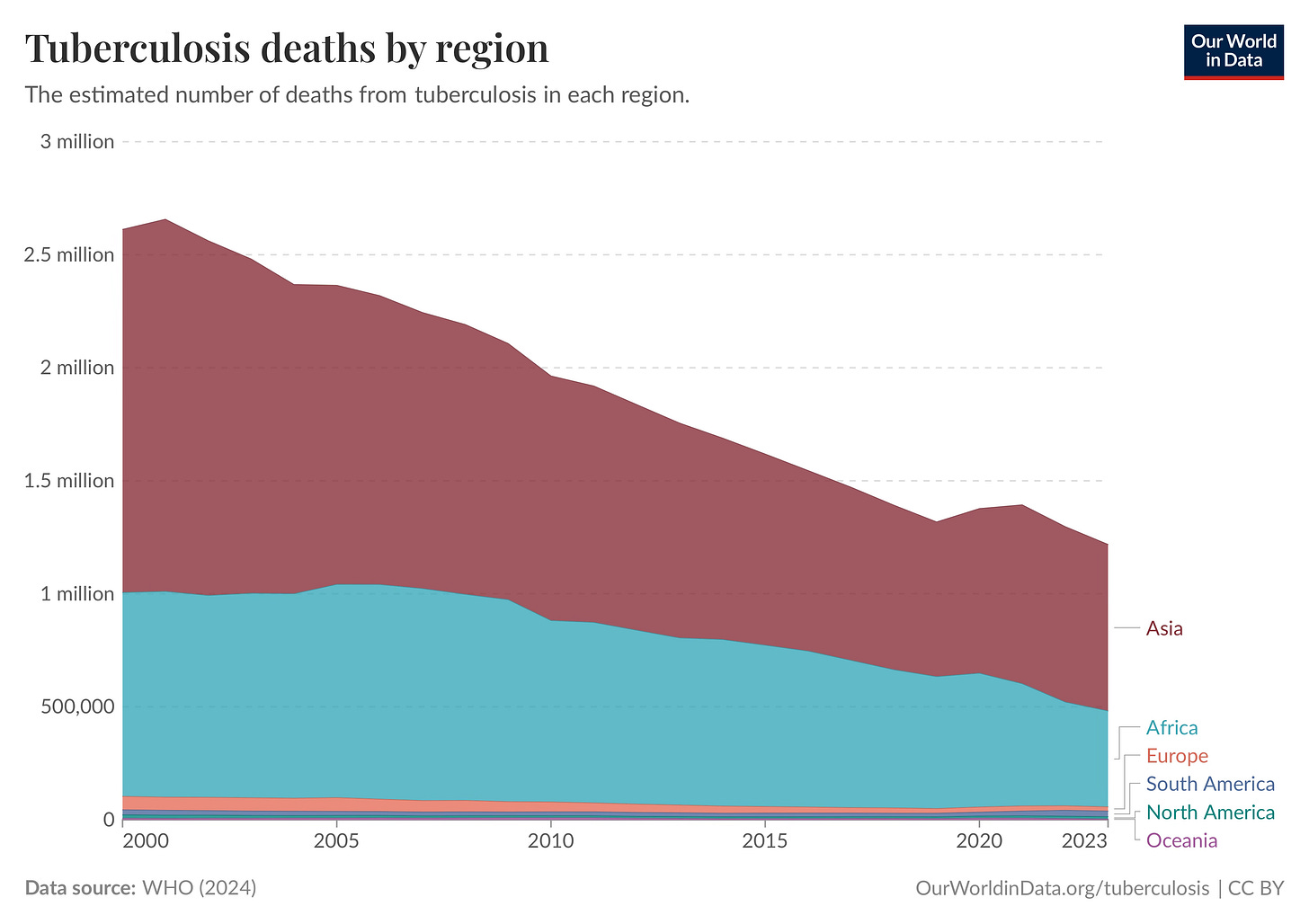

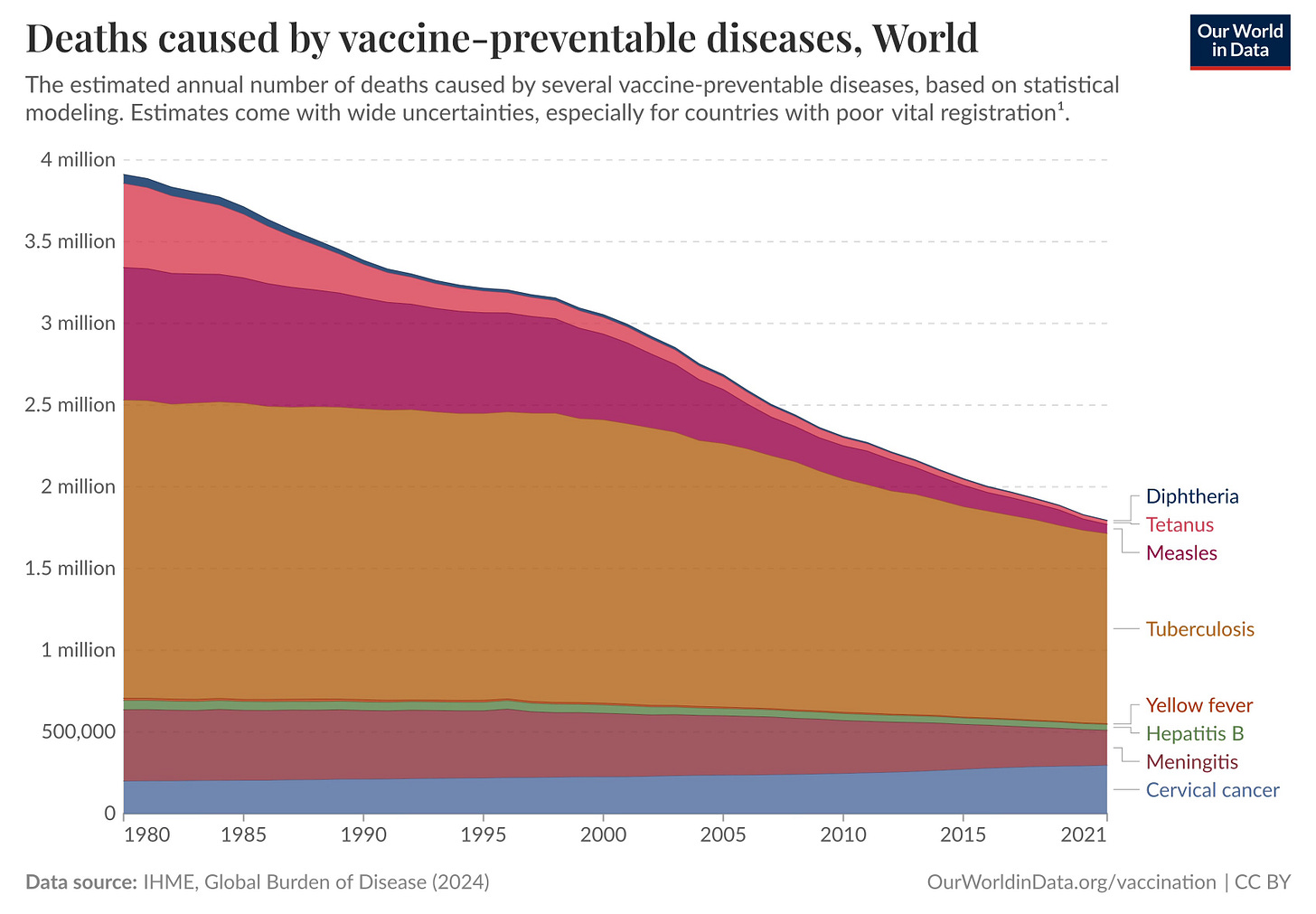

Clearly, TB has been a massive problem for a long time, ravaging the bodies of its victims without much concern for things like socio-economic status or geography. However, by the mid-twentieth century, following improved sanitation practices and the discovery of curative antibiotics, this had become a much more manageable disease in many countries. Why then does TB still kill over 1.2 million individuals every year (making it the largest infectious cause of mortality)? Why is this a hard problem for us to solve?

One of the reasons that makes TB so insidious is the nature of the pathogen itself. Mycobacterium tuberculosis grows slowly, replicating about once a day under ideal lab conditions, compared with minutes for many common bacteria. It takes time to grow because it wraps itself in an unusually fatty, waxy cell wall rich in mycolic acids, which makes it difficult for immune cells to penetrate. Instead, white-blood cells surround the bacteria, creating tissue balls called tubercles. Now, the bacteria enter slow or non-replicating states where the disease is uninfective and dormant to the point where the vast majority of people live and die oblivious to the presence of tuberculosis in their bodies: this is called latent TB. In India for example, the government estimates that “more than 40% of the population” has latent TB, yet active cases are much fewer. This does not make the disease harmless.

In about 5 to 10 percent of cases, the immune system cannot produce enough white blood cells to contain all the bacteria. M. tuberculosis then grows unchecked within the lungs or elsewhere, slowly overwhelming the body, causing a physical wasting away of tissue (earning it the name of “consumption”).4 Identifying these active cases early is notoriously difficult. Most patients today come from densely populated, low-income regions (which makes transmission via aerosols easy) where TB is already endemic. Malnutrition is common, so one of TB’s early symptoms, loss of appetite, may be misread as a welcome sign of feeling less hungry.5 This means that diagnosis is then delayed until the disease has progressed and patients are already highly infectious, ensuring that transmission continues.

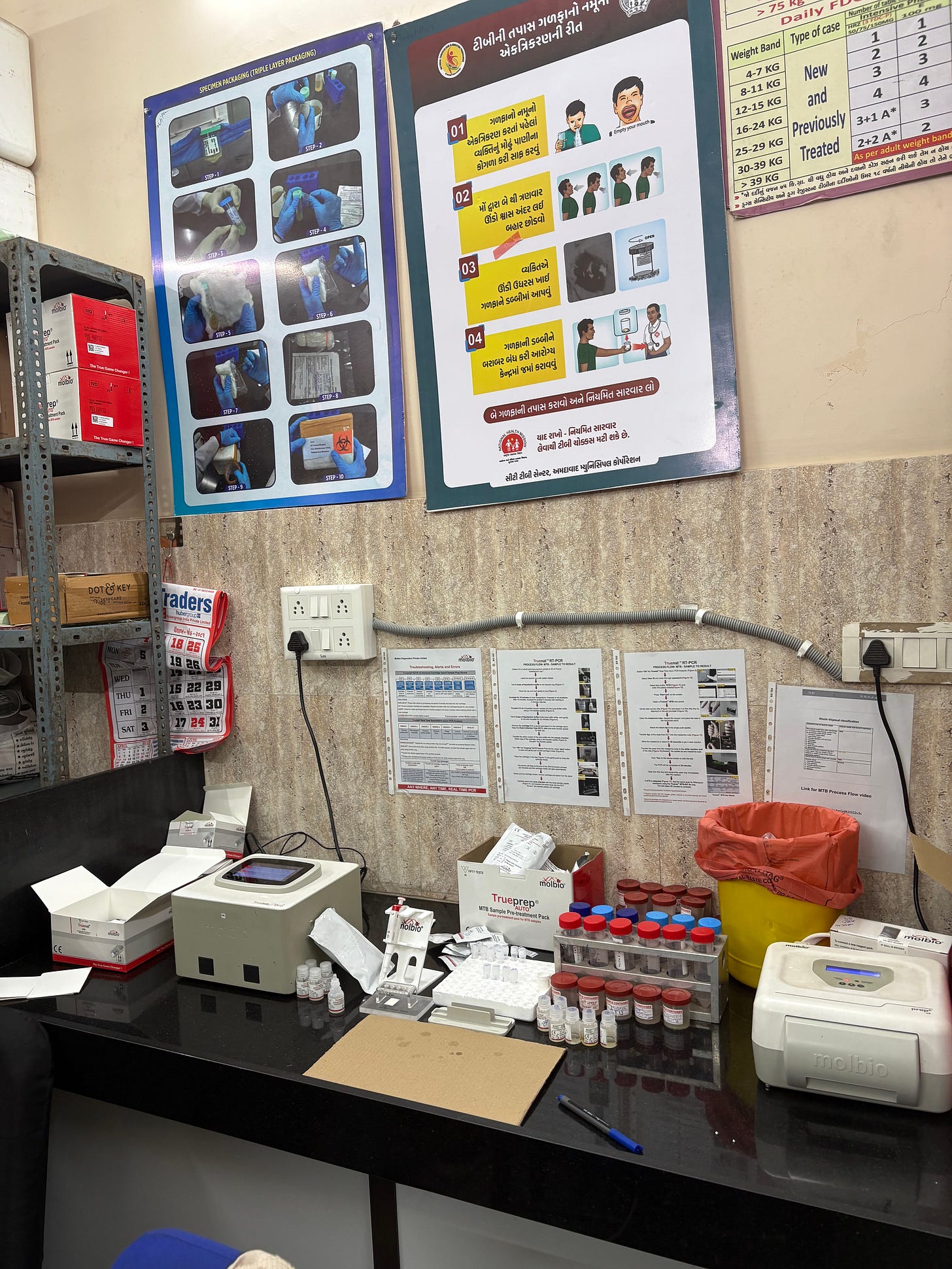

Even in hospitals, infection control can be inconsistent. When I visited a TB ward in a government-run clinic in India, the first thing I noticed was that no one, not even a single staff member or patient, wore a mask. Instead, in the crowded waiting rooms, coughing patients stood shoulder-to-shoulder with those awaiting unrelated care (including maternal screenings). Such settings allow the disease to continue spreading freely.

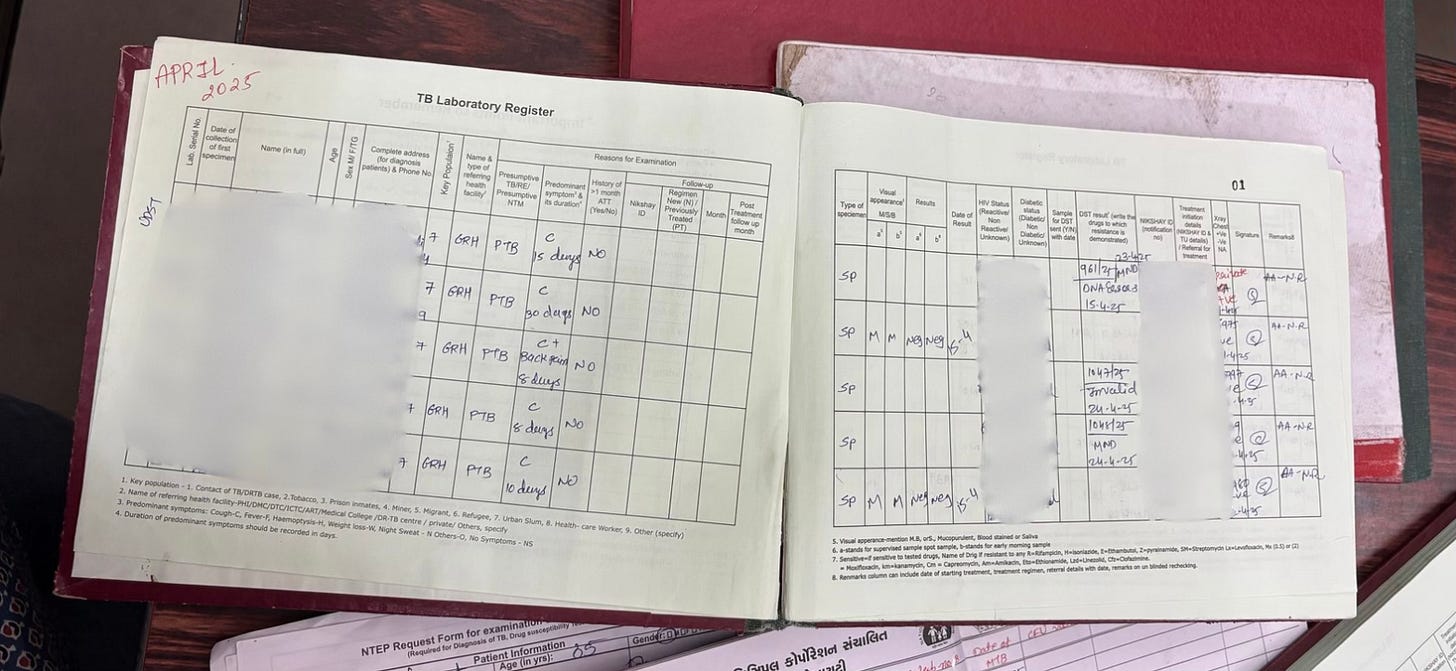

However, while infection control was sparse, I was pleasantly surprised to see that alongside chest X-Rays, the clinic took sputum cultures and tested each sample for drug-resistance before handing out the usual four-drug combination of antibiotics: rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE).6 This is a necessary advance, especially as the clinic reported that 20% of patients who are currently being treated came in with a drug-resistant variant of the disease and did not respond to the normal first-line interventions.7

Drug resistance is a predictable consequence of how M. tuberculosis interacts with treatment systems. The bacterium’s slow growth means that even with the right drugs, patients are forced to run a therapeutic marathon, taking the RIPE antibiotics daily for at least six months (or longer for more complicated cases). This prolonged timeline creates excessive challenges.

For one, almost nobody is prepared or able to isolate for the few weeks it takes for the disease to return to a dormant state – business as usual, despite having an active infection, increases community transmission. Patients also often stop treatment mid-way because of excessive side-effects such as nausea, reflux, and sudden onset of rampant hunger. Others pause the drugs once they start feeling better, unwilling to come into the clinic weekly to pick up their next few doses. Moreover, with hundreds of patients being treated at any given time, the hospital’s tracking mechanisms are also stretched thin, and patients inevitably fall through the cracks despite efforts to avoid unnecessary attrition. Regardless of cause, each interruption gives the surviving bacteria the chance to adapt, and over time, strains emerge that no longer respond to one or more of the primary drugs.

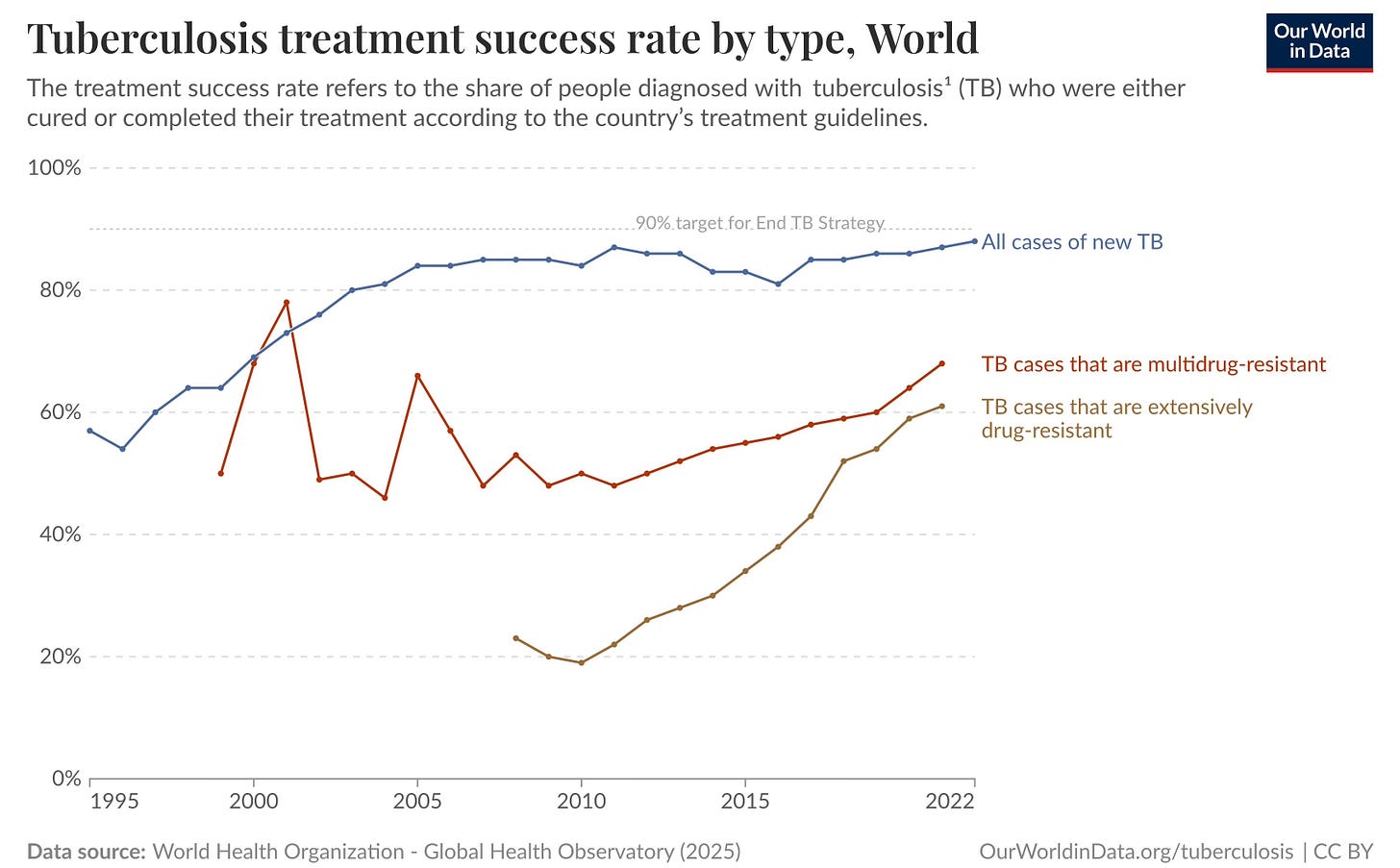

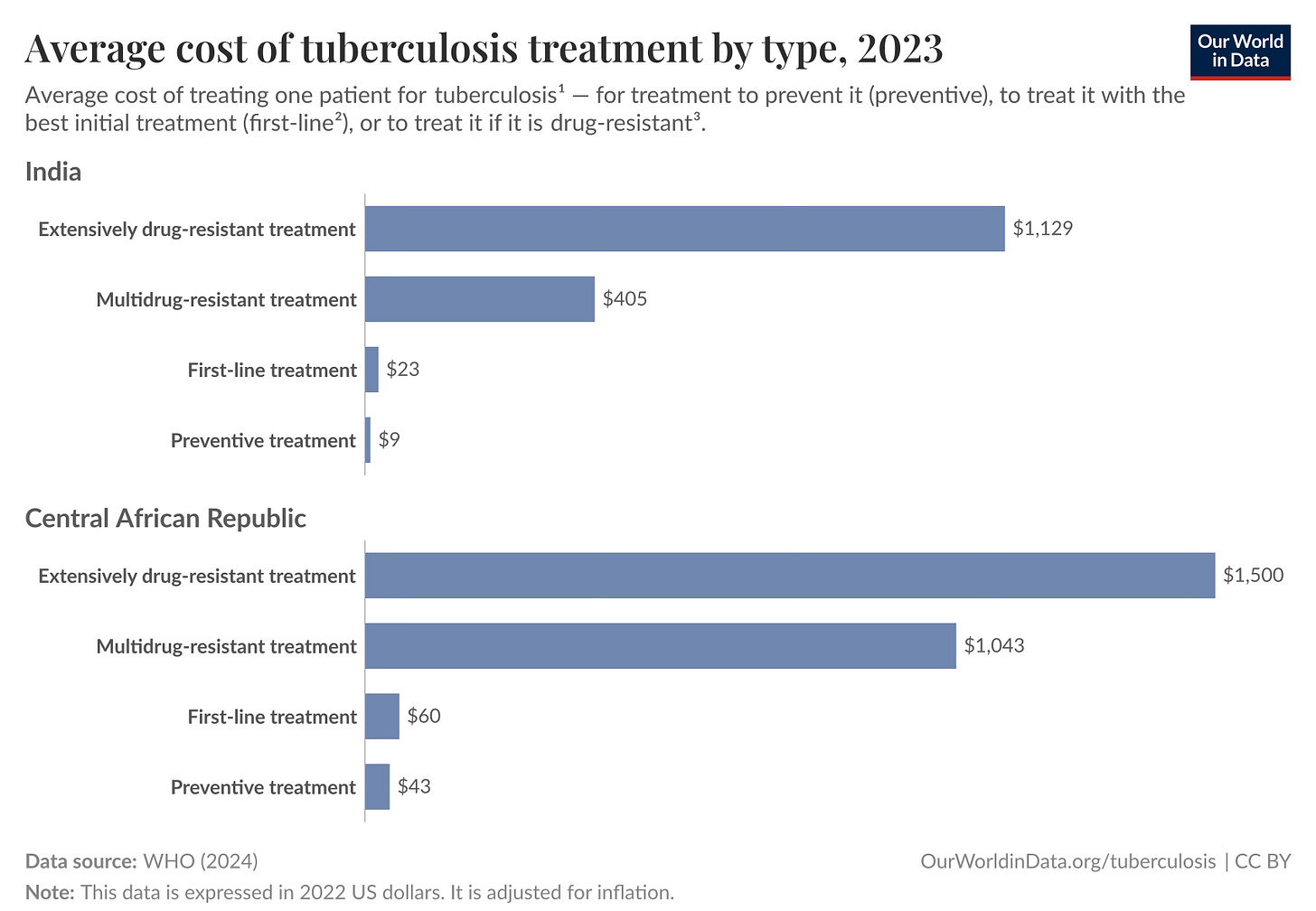

Once resistance sets in, the problem compounds. Treating multi drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) requires second-line antibiotics that are more toxic and less effective. Side effects ranging from hearing loss to kidney damage drive further non-adherence8, feeding the cycle of resistance. These regimens are also far more expensive, straining public health budgets that are already insufficient for universal coverage of drug-susceptible TB.

Tuberculosis creates a real financial burden on the patients and the systems designed to help them. Even as we continue finding ways of making testing cheaper and bringing down the price of drugs, the material realities of treatment add up. There is a real cost to missing work because of side effects, to commuting to the clinic on a weekly basis (if not more frequently) to pick up medication, to finding adequate nutrition, to staffing hospitals with enough personnel to track down infected individuals. This economic reality is part of the reason why tuberculosis, despite being entirely curable with proper treatment, continues to claim more lives than any other infectious disease – the systems designed to defeat it require sustained, substantial financial commitment that has proven elusive in practice.

The United States has historically provided about one-quarter of the total international funding for TB response with most of it being directed towards low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, since the recent dissolution of USAID and following the 90-day pause, a KFF analysis finds that of the 770 global health awards identified, 162 included TB activities, and 79% of those (TB-specific) programs were terminated. Similarly, the Center for Global Development estimates a 56% cut to the total dollar amount given by USAID for TB programs.

These cuts are expected to exact a real human toll: “An internal memorandum by the former acting Assistant Administrator for Global Health at USAID estimated a 28–32% increase in tuberculosis cases in the next year” if the funding cuts continue.9 Similarly, a more specific forecast from Asterisk Magazine uses Covid related disruptions as a proxy for how this shortfall might impact disease incidence and fatalities. In 2020 there was a 10-percent drop in global TB funding: this led to 59,000 additional TB-related deaths compared to the previous year.10 Today’s cuts are more concentrated (in LMICs) and may lead to 98,000–175,000 excess deaths in the first year as screening, diagnosis, drug delivery, and treatment support stall in the places most dependent on aid. Worse still, alongside increased mortality, these interruption to TB programs may increase the risk of people developing and transmitting the more difficult, drug-resistant strains of the infection.

Given the projections are correct, we are consciously condemning hundreds of thousands of human beings to a painful and preventable death. The prognosis is horrifying. Extensive weight loss, weakness, fevers, difficulty breathing, and coughing up blood all herald a long, slow, torturous death – and that is if the disease doesn't spread to the bone or brain. In Everything is Tuberculosis, John Green offers a particularly chilling description: “If left untreated, most people who develop active TB will eventually die of the disease. Their lungs collapse or fill with fluid. Scarring leaves so little healthy lung tissue that breathing becomes impossible. The infection spreads to the brain or spinal column. Or they suffer a sudden, uncontrollable hemorrhage, leading to a quick death as blood drowns the lungs.” This is a terrible way to die.

Moreover, per a 2019 analysis, roughly 25 percent of the world’s population has latent TB – we are truly not going to eradicate the illness anytime soon. In fact, it’s not really a thing of the past anywhere in the world. However, what many countries have accomplished is a TB incidence rate low enough that the scale of the disease is no longer worrying, and we have made strides in steadily whittling down incidence globally, too. Knowing that we are capable of doing so should encourage us to press on with fighting tuberculosis.

There is no new, flashy solution to the disease – the nature of the bacterium makes creating a high-efficacy vaccine challenging, and its prevalence in poorer markets means that there is a lack of financial incentives to invest heavily in R&D here. But even so, there is merit in staying the course and fighting this disease the old-fashioned way. In rolling up our sleeves to increase screening, expand BCG access, track drug-resistant variants, ensure sustained medication compliance, hand out and enforce masking – the un-sexy but vitally important stuff. The things that save lives.

Thanks to Mike Riggs, Abby ShalekBriski, Steven Adler, Andrew Burleson, Allison Lehman, Kelly Vedi, and Samarth Jajoo for feedback on drafts; and to the staff at Gomtipur Urban Health Center, Ahmedabad for providing observer access to a government funded TB ward.

Some reading that was particularly beneficial:

Our World in Data’s 3-part series on TB [here, here, and here]

John Green, Everything is Tuberculosis

Thomas Goetz, The Remedy: Robert Koch, Arthur Conan Doyle, and the Quest to Cure Tuberculosis

Vidya Krishnan, Phantom Plague: How Tuberculosis Shaped History

Saloni Dattani’s We don't have to sit back and just watch the horror unfold

As an additional note: I focused quite heavily on India as my model country for high-burden TB because living here provides me with insight on how things play out on the ground. If you have context on how TB infrastructure has been impacted in other countries (especially on the African continent) and would like to chat, please email me on hiya [at] mundane [dot] beauty.

Cover image: The Sick Child (Norwegian: Det syke barn). 1885-1886. Oil on canvas. 120 × 118.5 cm. Norwegian National Gallery (Oslo, Norway) [Wiki Media Commons]

Edited to fix copy errors.

Some necessary context: “BCG vaccine has a documented protective effect against meningitis and disseminated TB in children. It does not prevent primary infection and, more importantly, does not prevent reactivation of latent pulmonary infection, the principal source of bacillary spread in the community.” [source, WHO]

I would not read much into the 1-in-7 figure. There is almost certainly a lack of global data, and cause-of-death reporting was less robust. The figure serves primarily to underscore the severity of the disease worldwide, and especially in the West. From: Robert Koch, "Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose", Berliner Klinischen Wochenschrift 15 (April 10, 1882): 221. [English translation here]

The dramatic weight loss and loss of appetite that accompanies the disease is what earned it the old name of “consumption.”

From Everything is Tuberculosis: “It’s an illness of malnutrition that worsens malnutrition.”

This clinic only tested for Rimapicin sensitivity which let them know whether RIPE would be effective or not. If the case turned out to be complicated, they referred the patient out to the local medical college for further testing.

Such high resistance percentages are not typical. From the the Indian Council of Medical Research: “Drug resistance surveys in several states have indicated that the prevalence of MDR TB in India is 2–3 percent among new cases and 12-17 percent among reinfection cases.”

For a full list of drug induced toxicities in TB treatment see Table 1 in Seung, Kwonjune J., Salmaan Keshavjee, and Michael L. Rich. "Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis." Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 5, no. 9 (2015): a017863.

Not to mention: “The resulting disorder of these cuts raises the possibility of the diversion and rationing of previously distributed medications or transitions to poor-quality, non-bioequivalent, or second-line alternatives. This state of partial drug availability would be favourable for the emergence of drug resistance, most clearly for infections such as tuberculosis, for which USAID played an enormous role in ensuring consistent and extended combination treatment and for which there is a precedent for treatment interruption precipitated by social collapse leading to the emergence of resistance.” [Source: Lancet]

Larger context: “TB deaths, which had been falling by about 74,000 each year globally, increased by 59,000. Thus, a 10% reduction in funding led to approximately 133,000 additional deaths from TB after one year.”