The Bad Side of Medicine Comes for Us All

On early cancer diagnostics and people centered progress

This piece is a little different from my usual writing. It’s the essay I told myself I would never write, and once I began writing it I promised I would never publish it but here we are anyway.

My dad and I spend many long, lazy afternoons chatting about the mundane – in the still quiet of my childhood home, there are few other things to do. It is in these moments that he doles out little pieces of (always encouraging) advice, as fathers tend to do, even if it’s just to fill the silence.

“The world is your…shell,” he proclaimed sometime back. Naturally, I asked if he meant oyster? Oysters like the sea creatures that are farmed fresh, cracked open on a bed of ice, and served on tall towers of silverware with wedges of lemon. It was a delicacy, I explained, an expensive one that was seldom eaten in our landlocked hometown. One cracks open the mollusk, garnishing the gelatinous creature before gulping it down whole.

He recoiled at the image, now desperately searching for a different analogy, but I had made his point for him. When you are twenty-something, the world does feel conquerable, beckoning you to lift it off its platter and into the palm of your hands. It fits rather conveniently and you are all but set to greedily devour its flesh.

I had felt this way before, spending three exceedingly happy years in New York untroubled by the biting cold of northeast winters. I read incredible books in beautiful libraries, ran into my friends all the time, and worked on esoteric projects – in a sense, I was invincible.

Then, mid-November last year, my favourite person in the world, my dad, got cancer. Incurable cancer. Suddenly, time that seemed infinite collapsed into a matter of years. That night, in my dreams, the oyster grew larger and larger till I was cradling it with both hands, trying desperately to hold on. I was certain that it would soon become crushingly big and, without dad’s steadfast presence, I would be left carrying its weight all alone.

So I did what anyone in my position would do, I packed up my bags and moved back to India.1 There was no plan but to stretch the thread of time, to talk about oysters big and small.

A year on, I wish I could say that we are out of the woods, but treatment for multiple myeloma (MM), as I have learnt, is a marathon. That is to say, this piece was not written with the intention of post-chemo catharsis (in fact, putting this out there is incredibly uncomfortable), but to think through cancer in an undetached manner.

Because it truly is one thing to read about grade-3 neutropenia2 as a potential side effect of the drugs and another to scrub your hands raw with disinfectant lest you bring home a usually harmless variant of the common cold. Owl Posting put it in rather beautifully grim terms:

“At some point you surely have to understand that you have been, thus far, lucky enough to have spent your entire life on the good side of medicine. In a very nice room, one in which every disease, condition, or malady had a very smart clinician on staff to immediately administer the cure. But one day, you’ll be shown glimpses of a far worse room, the bad side of medicine, ushered into an area of healthcare where nobody actually understands what is going on.”

With Myeloma it is a race against time (albeit a rather successful one thus far), to find novel therapeutics that keep you away from the “bad side of medicine.” Over time the malignancy slowly becomes refractory to whatever drug regimen worked previously and when the cancer inevitably relapses, you are left scrambling for something new.

But drug discovery is a relatively slow process. Although I have known this for a while, these days when I scroll through StatNews, there is a different sort of urgency on my mind – I am both in awe of the progress that is to come in but a few short years and saddened thinking about all the people who won’t make it that far, those who are already condemned to a place where medicine has no answers.

It is very true that the mountain of stuff we do know about disease and medicine is but a spot on the horizon when compared to the chasm of ignorance that surrounds it. Moreover, there is an ominous certainty that all of us will fall off the cliff at some point and spend our days grappling in the dark, hoping to make it back to the peak.

With cancer, each year about 10 million individuals inevitably lose their foothold on the mountain of medical miracle. That is a big number, and it’s difficult to truly wrap our heads around such suffering but we must realize that there are real people who make up that figure – people that you and I may even love.

Then, to exhaust the analogy, should we not do everything possible to try and stay on the mountain? Should we not work to test for and identify illness before the rope snaps off, to identify the durability of our gear, to hang on to the good side for as long as possible?

Most patients with multiple myeloma are diagnosed quite late.3 This is because, while the disease eats away at your bones and weakens your immune system by crowding out healthy blood cells, there is no real mortal danger in the short term. Instead, you are hit by run-of-the-mill symptoms, such as aching bones and fatigue. What person over 50 hasn’t complained of being tired?

In fact, it can take over 6 months4 of chronic pain to receive a diagnosis for MM by which time almost 9 percent of individuals are hit by cancer-related fractures. This is preventable suffering.

My dad, thankfully, did not experience this and today he has favorable prognostic outcomes solely because he was diagnosed early. Because we got lucky. Because his position in the world, as a doctor, helped him to identify and verbalize the difference between muscle pain and bone pain. This understanding ultimately allowed him to use the resources at his disposal and slip into the MRI machine on his lunch break to scan for the mild back pain he was experiencing. Had it been anyone else with his presentation, it would certainly have taken months longer. Months where the vulturous latent tuberculosis in his body would have wreaked havoc on his compromised immune system and the conversation here would be significantly different.

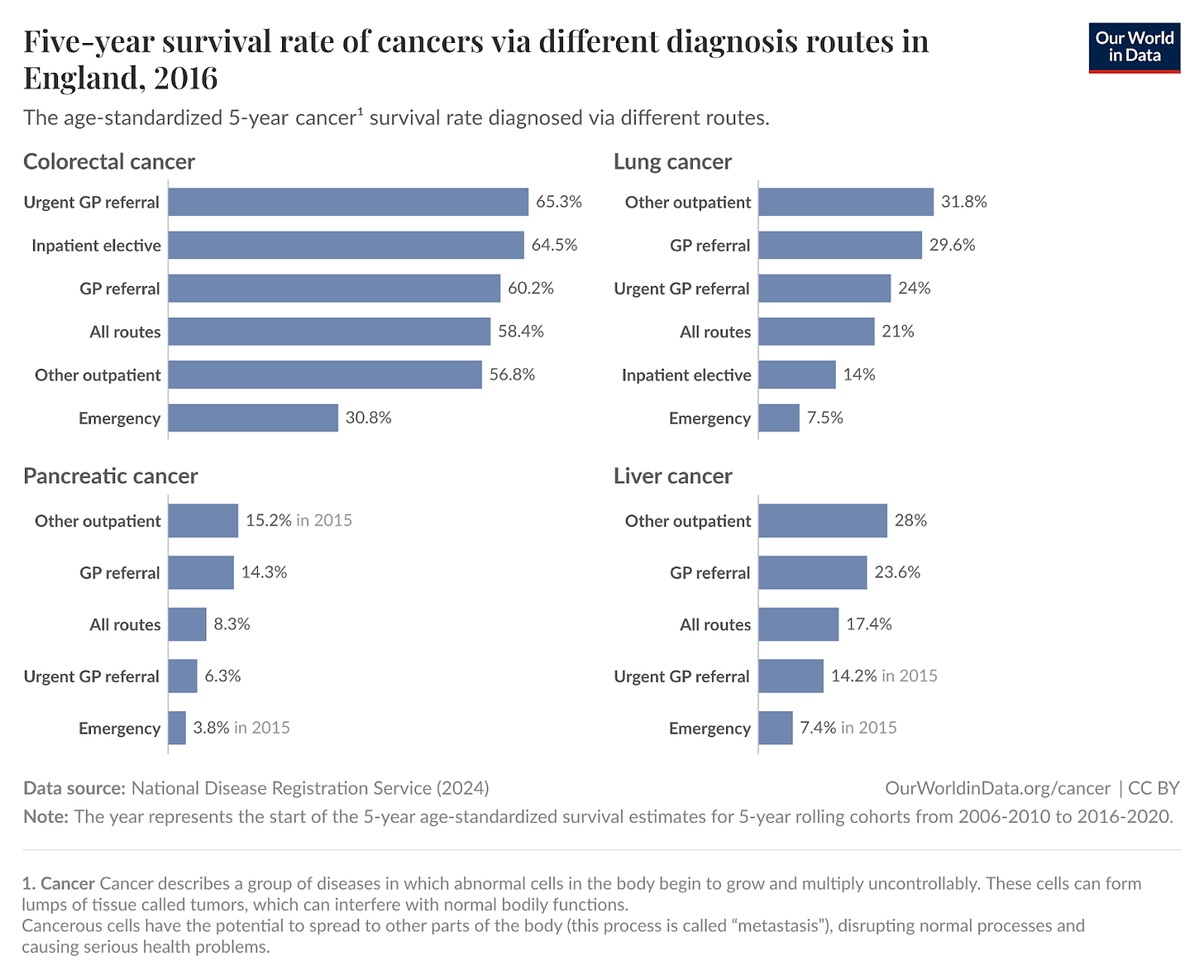

Unfortunately, this is a reality for patients with many other types of cancer. Moreover, these are often malignancies where diagnosis delays due to vague symptom presentation have much graver consequences. For example, with ovarian cancer, tumor growth that is “confined to the ovaries (stage I) can be cured in up to 90% of patients, and disease confined to the pelvis (Stage II) is associated with a 5-year survival of 70%. However, disease that has spread beyond the pelvis (stage III-IV) has a long-term survival rate of 20% or less. Only 20% of ovarian cancers are currently diagnosed in stage I-II.”

Pancreatic cancer is even worse: “The small percentage of patients (10–15 %) diagnosed to present with resectable PC, primary surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is the only possible way they may survive long term. However, because the disease presents with minimal symptoms, 40–50 % of PC patients receive a diagnosis of locally advanced and incurable forms. An additional 40 % would present with stage IV metastatic disease at diagnosis.” To put it bleakly, the five-year survival rate for this cancer is ~12%. Those terrible odds are the best we can currently offer because most pancreatic malignancies are caught too late.

These deaths can be prevented – we have known for a while now that early detection drastically increases survival odds across a variety of different cancers. Moreover, we can see this works with the case of breast cancer, which is perhaps the most well-known success story for early detection. For women diagnosed with localized breast cancer, the 5-year relative survival rate is an exceptional 99%. Due to effective screening programs like mammography, approximately two-thirds (66.5%) of all breast cancer cases in the United States are diagnosed at this highly treatable stage. However, for the subset of women whose cancer is not detected until it has reached a distant stage, the 5-year survival rate falls to just 32.9%.

Such examples tell us that perhaps the primary determinant of mortality is not necessarily the organ of origin but how far the cancer has metastasized – treatment becomes exponentially more challenging once a tumor has seeded itself in distant organs like the lungs, liver, or bones. Therefore, any technology that can reliably and systematically detect cancer before this metastatic cascade occurs is as necessary for true cancer control as are effective late-stage therapeutics.

However, as we have seen, diagnosis is difficult especially in cases where symptoms are inconspicuous and non-invasive, inexpensive testing unavailable.5 It is both unfeasible and unpleasant, for example, to have at risk patients undergo annual PET scans to catch early stage tumors. Instead, what we need is ubiquitous blood based testing.

“Most cancers are not screened because their prevalence in the general population is too low to justify screening programmes on an individual cancer basis. However, the number of people that need to be screened to detect cancer goes down when prevalences are combined; that is, when multiple cancers are screened for in a single test. Because all cells in the body have access to the circulatory system (directly or indirectly), blood is an attractive analyte for a multicancer test.”6

There is encouraging progress in this direction with Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) tests which are a promising way to detect cancer’s molecular signature in a simple blood draw, long before symptoms appear. These liquid biopsies work by analyzing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) that tumors shed into the bloodstream, examining the DNA methylation patterns (chemical tags that regulate gene activity and serve as a unique fingerprint for different cancer types). More importantly, this method can simultaneously screen for dozens of cancers, including ovarian and pancreatic cancer that currently lack effective early detection methods.7

GRAIL, in particular, has developed the Galleri test which is the most clinically advanced MCED on the market, and can detect signals from over 50 cancer types. In a paper from 2020 the company writes, “In the validation data set, the multi-cancer early detection test had a false positive rate of 0.7% and an overall test sensitivity (true positive rate) of 54.9%. Sensitivity… for all cancer samples with known tumour stage were: stage I (n = 185), 18%; stage II (n = 166), 43% ; stage III (n = 134), 81%; and stage IV (n = 148), 93%.”8 There is also a larger randomized controlled trial in the works with the NHS, with 140,000 participants, and is expected to report results in 2026.

Yet despite this promise, MCED tests face resistance from segments of the medical community. The concerns are familiar echoes from previous screening debates: What about false positives causing unnecessary anxiety and procedures? Won’t these tests detect indolent cancers that would never have caused harm, leading to overtreatment? Where is the proof they actually reduce mortality? And aren’t they too expensive to be equitable?

These are not unreasonable questions, especially following the case of the PSA [blood] test for prostate cancer, for instance, which led to widespread overdiagnosis of slow-growing tumors that would never have threatened an (older) patient’s life. Critics also argue that stage-shift (diagnosing cancers at earlier stages) is an insufficient endpoint over true mortality benefit. And overall it would be fair to hold the opinion that the technology is yet to finish maturing: here, the results of the NHS-Galleri trial will help accurately pinpoint false-positive rates and real benefits from early detection.

However, in the meantime, I strongly believe we should avoid the kind of extreme rhetoric that has emerged in some quarters. This comment, for example, claims parallels between GRAIL and Theranos, suggesting that investor centered hype is leading us down a similar path of corporate fraud and collapse. They then go so far as to call for Galleri’s complete withdrawal from the market, arguing that until we fully understand its capabilities and potential harms, it should not be available at all.9

Such writing reads as short-sighted and biased, and most importantly takes away agency from individuals. If my dad had been screening for his m-protein levels regularly (blood based test here too) a decade ago, we would have known he had MGUS, the harmless precursor to myeloma. We would have monitored things closely, and when he progressed to Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM), the more indolent version, we would have been ready. There would never have been symptoms, but about half of all SMM cases progress to active disease within 5 years. We would have had time to plan. Time that we did not have last November, when my parents kept his diagnosis from me for two weeks while I applied to PhD programs – two weeks of normal-sounding phone calls so that I could selfishly concentrate on myself, unaware that my world would break apart.

I also bring up SMM because it helps defeat the argument that early diagnosis is pointless without treatment options. For decades, the standard approach for patients who (by some stroke of luck) were diagnosed with the precursor disease was “wait and watch,” regular monitoring so that medical teams could begin treatment if and when symptomatic disease with organ damage, bone fractures, and kidney failure, arose. But in December 2024, the AQUILA trial demonstrated that early intervention with daratumumab (a monoclonal antibody) significantly lowered the risk of progression (to full blown MM) and death compared to active monitoring alone. Meta-analysis shows that early treatment produces a 60% reduced risk for disease progression and a 45% lower risk of death.

Similar success can be replicated across other cancers if we identify high-risk patients early. Moreover, early diagnosis can also help reshape pharmaceutical incentives to make prevention profitable. The larger economic case follows naturally. Treatment costs for late-stage cancer patients are up to 7 times higher than for those diagnosed early and per the WHO, early-stage treatment is 2 to 4 times cheaper than treating advanced disease.10 For colorectal cancer alone, “increasing screening prevalence to 70% among adults aged 50-64 could reduce Medicare spending by $14 billion by 2050.” All of this is not even accounting for the economic opportunity cost of getting and treating cancer for the individuals at the center of it all.

In every respect, I believe that knowing is always better than not knowing. There are many who will share this opinion with me and for them, electing to take something like the Galleri test might still be worth it despite its perceived short-term drawbacks. Patients can make informed decisions about imperfect information – they should have the choice to do so, it would be deeply paternalistic to take that option away from them.

Early detection is not a luxury. It is the difference between cure and palliation, between manageable treatment and devastating (co)morbidity, between lives saved and lives lost. It is the difference between having a decade of good years with my dad and not.

Living in a world with cheap, non-invasive, ubiquitous diagnostics would be one where everyone had the opportunity my dad did and not through privilege or luck. This is the true purpose of technological progress: to give people the crucial ability to make informed decisions about their body, to try and live a good life despite peaking at the bad side of medicine.

With much gratitude to Emma McAleavy, Mike Riggs, Abby ShalekBriski, and Samarth Jajoo for their measured feedback and unbounded support.

Note: I will be in the Bay Area for the Roots of Progress event later this week (16-19th Oct). If you will also be around then, free to reach out and we can get coffee!

Edited for typos.

When drugs kill off healthy white blood cells en-masse, specifically neutrophils, and make the patient susceptible to infections.

Often diagnosed when the patient already has the cancer rather than the precursor stages of Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM), and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unspecified Significance (MGUS). Catching disease early can help patients use lower dose Rx to avoid/delay progression to full blown cancer - significantly increasing overall survival.

6 months is the general ballpark number but again this varies by source, for example patients in this study saw a median time to diagnosis of 4-6 months.

This is not the case with myeloma which is a blood cancer and can already be screened for through normal blood based testing.

Joshua J. Ofman et al., “GRAIL and the Quest for Earlier Multi-Cancer Detection,” Nature Portfolio, 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-020-00079-y

Although we do have the CA125 blood test for Ovarian cancer, it has its own limitations: “CA-125 has a known limitation in terms of its diagnostic performance particularly for early-stage disease. It has been reported to be elevated only in 47% of women with early stage ovarian cancer but is elevated in 80–90% of patients with advanced stage disease. However, it can also be elevated in some benign conditions of the ovary including ovarian endometrioma. These findings were illustrated further by others who also reported a poor sensitivity and specificity when the test was used alone.” [Source]

95% CI removed for brevity, full quote as follows: In the validation data set, the multi-cancer early detection test had a false positive rate of 0.7% and an overall test sensitivity (true positive rate) of 54.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 51.0–58.8%). Sensitivity and 95% CIs by stage for all cancer samples with known tumour stage were: stage I (n = 185), 18% (13–25%); stage II (n = 166), 43% (35–51%); stage III (n = 134), 81% (73–87%); and stage IV (n = 148), 93% (87–96%).”

The quote was followed by this commentary which correctly identifies my unease: “The Letter to the Editor, stated that a recent prospective clinical trial using the Galleri MultiCancer Detection Test was temporarily put on hold [1]. This may give the impression that the trial will not be continued. However, the NHS website states: After the trial, we will have a much better understanding of how well the Galleri test works in the NHS. If it does work, then it could be used in the NHS in the future (like breast screening or bowel screening, but for many different types of cancer). If the Galleri test does not work well in this setting, then we will still have learned important information about what research needs to be done in the future to improve cancer screening [2]. The letter to the editor [1] contains the sentence: The Grail case has some similarities to the Theranos story, which sent some executives to jail and led to company bankruptcy. This sentence could be misinterpreted as a comparison with Theranos, and such a comparison is not accurate.”

Also see: Nora McGarvey et al., “Increased Healthcare Costs by Later Stage Cancer Diagnosis,” BMC Health Services Research 22, no. 1 (2022): 1155, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08457-6.

Thank you for sharing this, Hiya. I hope your dad's health is better soon.

I am so glad you wrote this, Hiya. I participated in the US-based Galleri trial last year, and it was so meaningful to do a small part in hopefully bringing broad-based early diagnostics to people who want them. And as someone in my 50s, I'd love to have the option to pay even out-of-pocket for this test every year or two, because like you, I want to know--and I do think that knowledge creates opportunity. More people who know they have early stages of a disease means more people pushing for faster, better clinical trials and new medication that can stop disease progression.