Notes: Fertility in India

On being a participant in the crisis + some big ideas

One particular thing that I have noticed about the debate on fertility is the distance with which the ideas are (often, not always) presented. Publications use terms like “crisis,” “demographic suicide,” and “career penalty” easily – treating it like yet another economics problem to be solved, a need to cushion against the perils of an aging population, without really empathizing with or catering to the women who inevitably become central to the question at hand.

Looking back, this is probably one of the reason why I failed to engage with the discourse so far (and this is true for many of my friends too). I find it uncomfortable to read about the many reasons for declining fertility which can, in part, be attributed to the increasing access to education, employment, and the internet for women. Irrational as it may be, it feels callous to critique the choice that women have today to take on ambitious, fulfilling, if ‘greedy careers’ even if it comes at the cost of late marriages and fewer children. [This is perhaps the reason why Ruxandra Teslo’s article, Fertility on Demand, was so refreshing to read because it argued for choice. A ‘both and’ paradigm that allowed the reader to envision a future where she could both have the career she wants and all the children she desires.]

For the pro-natal argument to succeed, it needs to be presented with more empathy. Less as a hypothetical and with more care for the very individuals who might be most affected. My primary reason for thinking this is true comes from growing up in India and interacting rather fluidly with women across a wide range on the age and socio-economic axes. That is to say, this is a limited snapshot (hence ‘Notes’) but hopefully an interesting one.

Some context first:

Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in India is sliding and recently hit 1.9 [global replacement rate is 2.1 children per woman]

This decline is striking because:

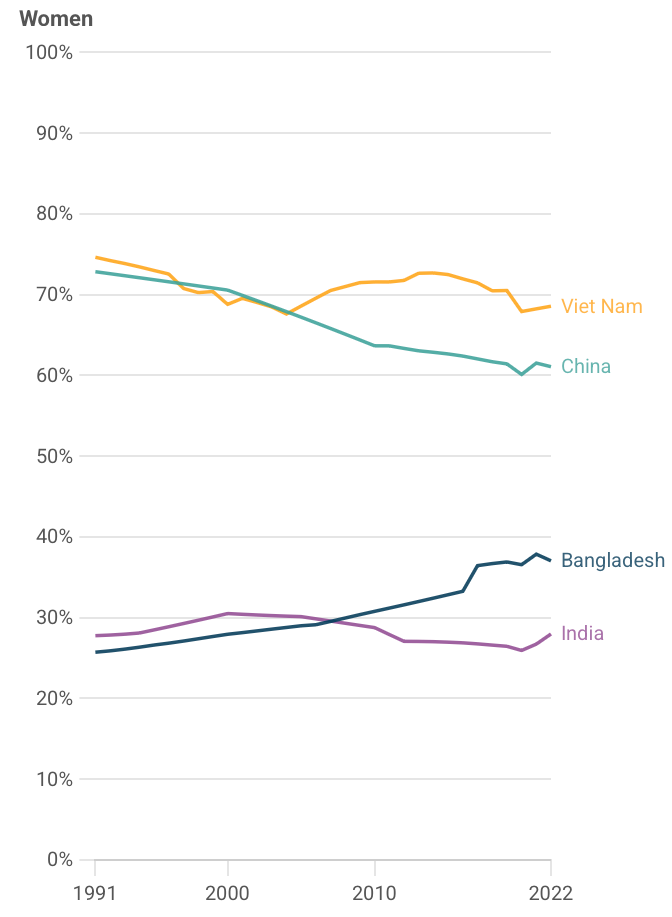

Indian female labour force participation (LFPR) is not particularly high even when compared to demographically similar countries. Although this does not hold among the diaspora (i.e. once women leave India, LFPR increases quite a bit: see Alice Evans excellent article on How Migration Enables Love & Economic Prosperity).

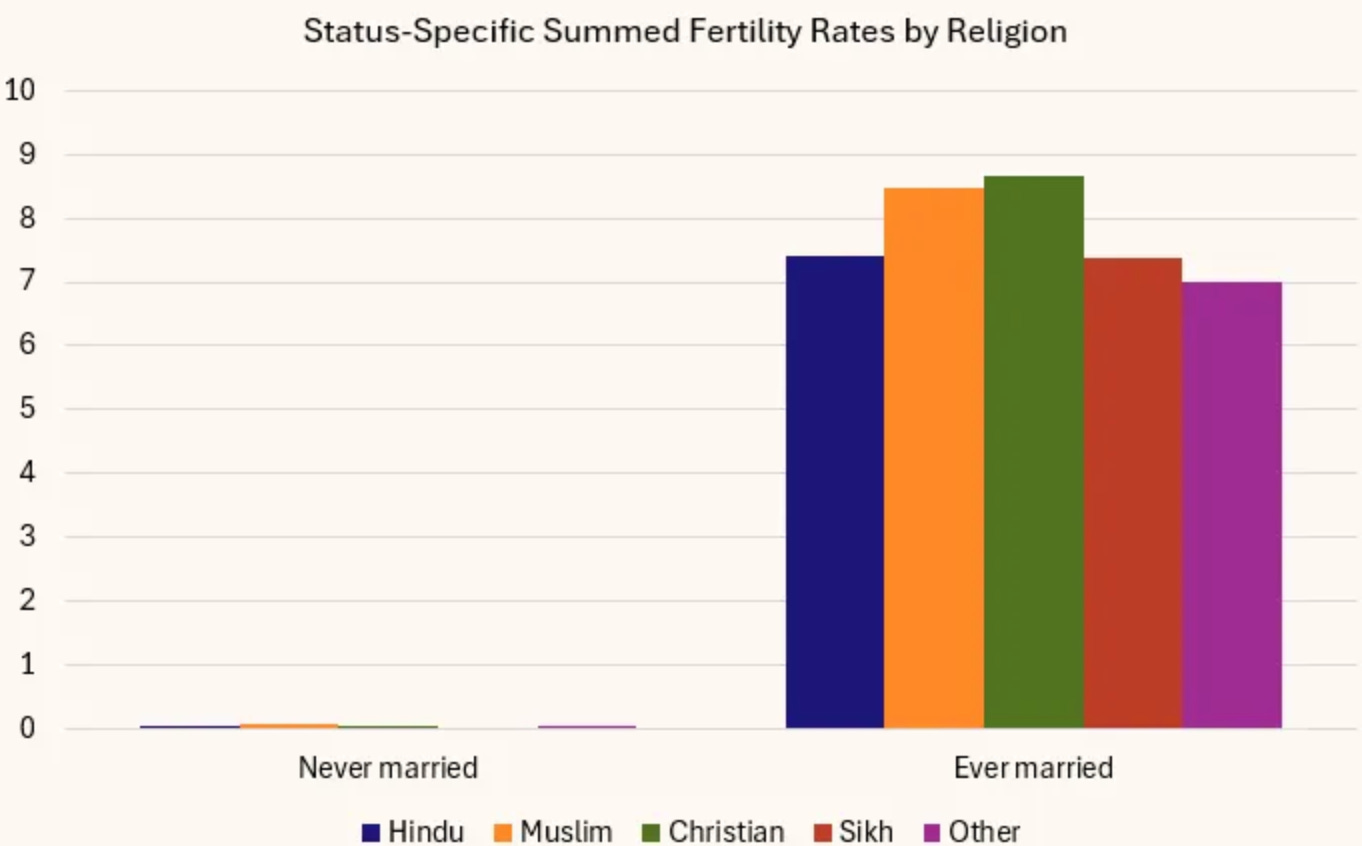

Female Labor Force Participation, from Data for India Marriage rates continue to remain relatively high. As Alice Evans notes coupling is somewhat stable in South Asia because of caste-networks, arranged marriages, and social stigma against divorce (and late-to-marry young people). Furthermore, “between 1992-93 and 2019-2021, changes in non-marital fertility explain 0% of fertility change because it’s more-or-less zero in both cases.” My personal takeaway from this is that, at-least in broad terms, we cannot ascribe that much weight to the falling fertility is caused by falling coupling logic when talking about India – rather people are choosing to have less children within marriages.

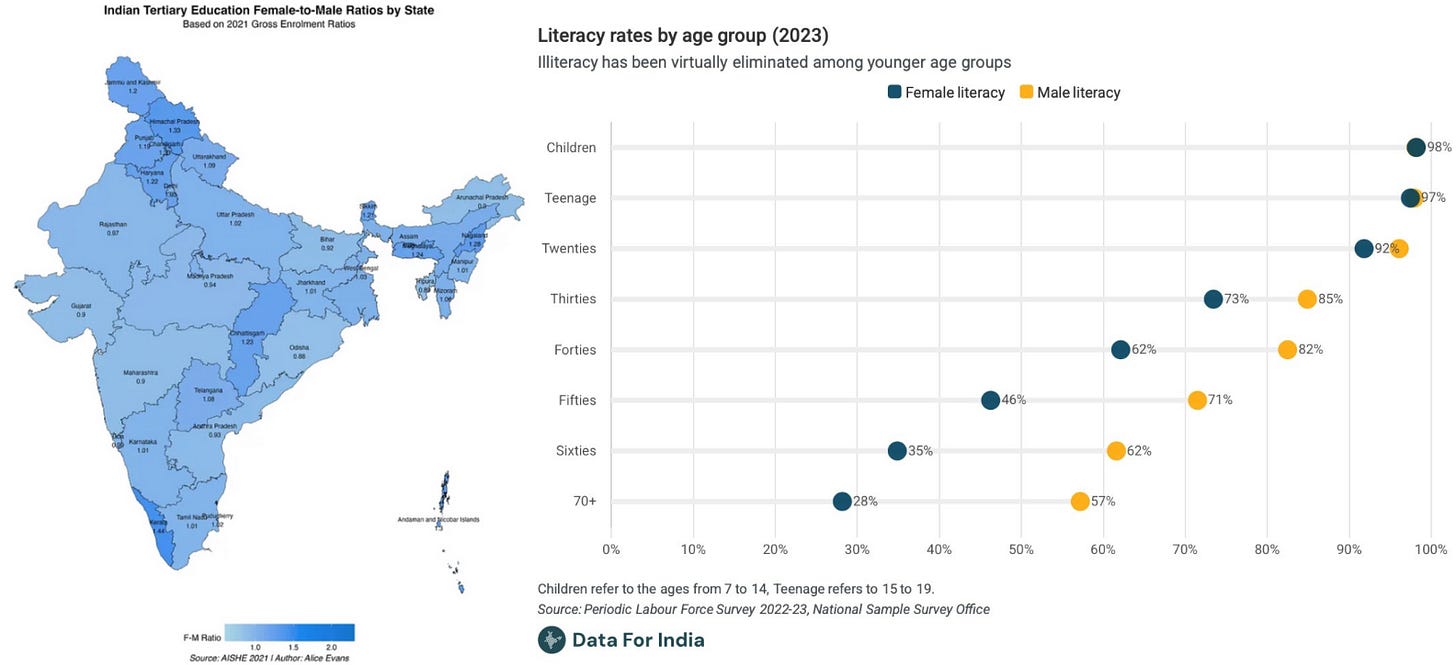

Quote above and graph from Lyman Stone’s article Does Marriage Matter in India where he makes an interesting if contrarian argument re: high rates of marriage in India. Female literacy rate in the country is rising and the gender gap between in educational attainment is dwindling:

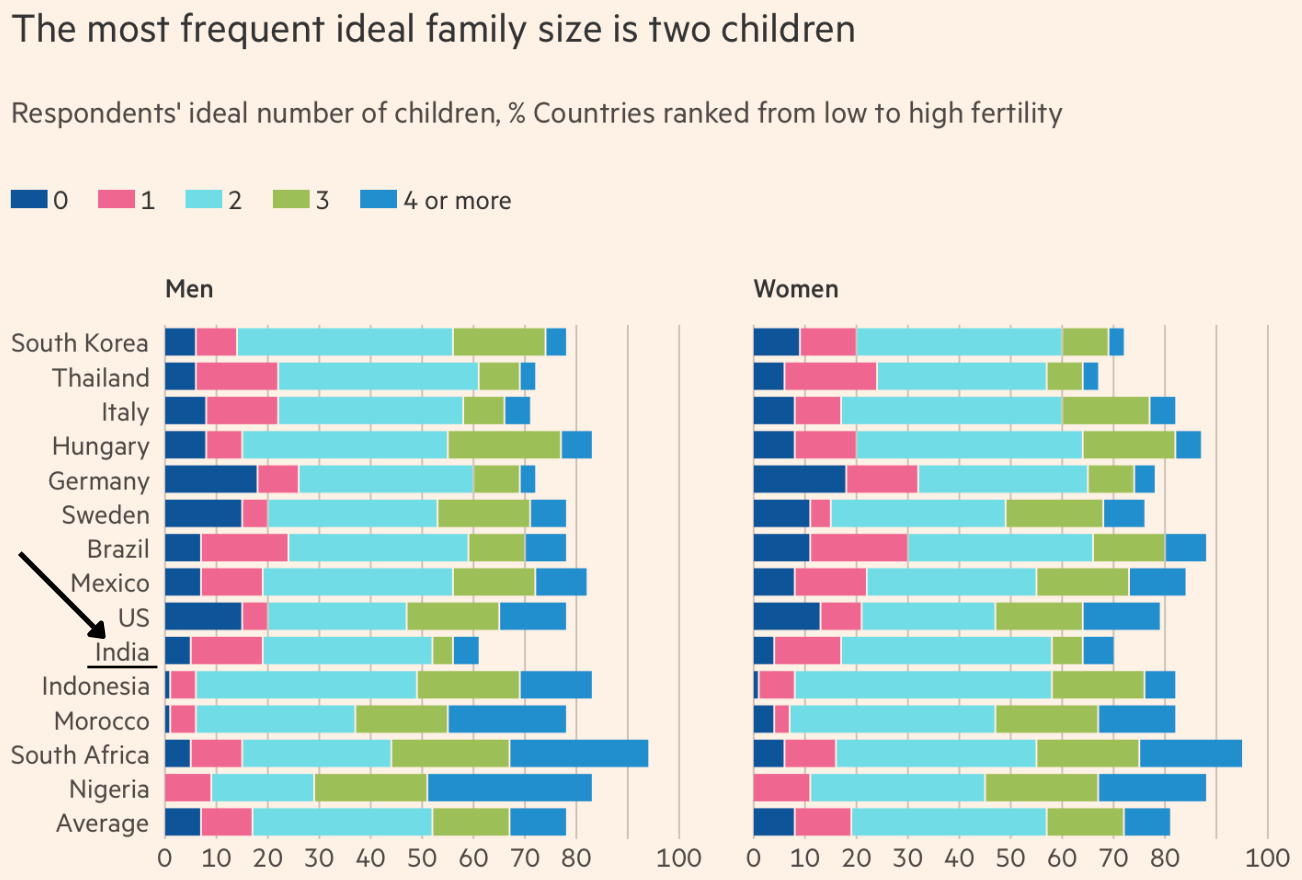

In India, like in most countries, there is a preference for two children. This is especially important because “in the Indian context, childlessness accounts for only 6% of the difference between high-fertility and below-replacement districts” [source here] – i.e. again, the main driver of lower fertility in India is an increase in women having less children not women having no children.

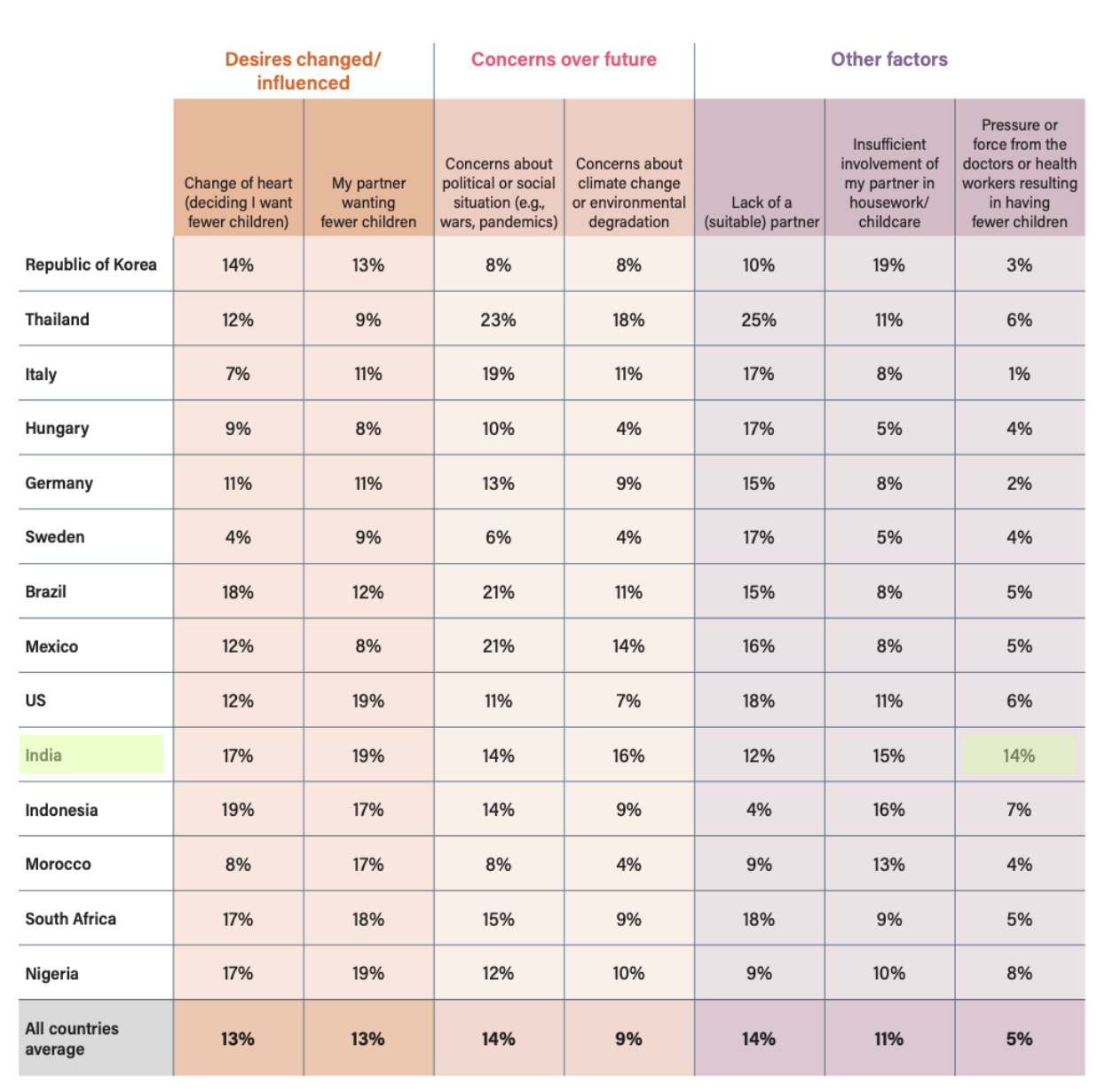

Source: FT And interestingly, part of this tendency can be ascribed to pressure from health-care workers (and society at large) to have fewer children. [Tangentially, another graph from the same source shows how women in India don’t end-up with their desired family size because of limited access to fertility care at higher than average percentages.]

To quickly summarize: Indian women are increasingly educated, matching male counterparts, though this hasn’t translated to workforce participation. They continue marrying at high rates due to social pressure, and married couples account for virtually all people who are parents. Both women and men converge on two-child households, influenced by a society-wide push toward smaller families.

Many of the facts presented above can be ascribed to a pervasive tendency towards female seclusion and honor in India. This is very much an oversimplification, but it is not false to say that:

Educated women bring credentials and prestige to the family.

Employed women have financial freedom, agency, and move outside the domestic sphere in spaces where traditional gendered interaction is broken down.

Limiting employment thus helps curb career ambitions that might delay marriage and prevents romantic encounters where women might choose their own partners

From the BBC: “In a 2018 survey of more than 160,000 households, 93% of married Indians said that theirs was an arranged marriage. Just 3% had a "love marriage" and another 2% described theirs as a "love-cum-arranged marriage", which usually indicates that the relationship was set up by the families, and then the couple agreed to get married.”

(Though anecdotally, many romantic relationships are retroactively presented as family-arranged to preserve honor).

Caste restricted marriages are important for the honor of the family, for maintaining patrilineal ties, for business interests and so on.

Therefore we can say that an educated woman fetches better marital prospects for the family and her lack of employment helps maintain purity culture as the status-quo. But why smaller families?

I think much of the credit should be ascribed to the immense success of the “Hum do, Hamare do” campaign. Literally translating to “two of us, and two of ours”, this state sanctioned family planning initiative was aimed at eliminating excessive poverty courtesy of large families. A modernizing initiative of sorts that played out on all levels of society:

They [Indian bureaucrats] invented methods of communication that steered the popular imagination of the family towards a specific direction: the small, cohesive unit that came to epitomize postcolonial modernity. Their success may be gauged from the fact that the family of four contained in the red triangle not only reflected the state’s need to control birth rates, but also came to represent an aspirational standard of life for the middle classes. The idealized “small family” was one that could afford modern comforts, amenities and leisurely activities. [Source here]

Although never an authoritarian push like China’s one-child policy, the government did definitely succeeded in “steering the popular imagination” of the country. I want to present two example of how they did so by looking at television advertisements from the 1960’s.

Now some context. These clips probably ran on Doordarshan which was India’s primary television channel and a national phenomenon. Per my father, who has fond memories of the channel from the 70’s:

It had limited hours of run time and was seldom on during the 9-5 slot when most people were working.

There was a fixed telecast schedule most days with 15 minutes of news followed by 30 minutes to an hour of a show of some sort that came with at least 2 ad breaks.

TV thus was firmly a family event where everyone in the community waited and watched together: predictable, high reach, limited choice.

It is within these circumstances that we see “Wives and Wives,” a full color animated short that was narrated in English – it first aired in 1962. I urge you to take the four minutes necessary to watch the full clip [linked here].

In essence, a man is picking out is his ideal wife through a biodata (a document akin to a relationship resume that is still in use today). He finds two women to his liking, both more or less identical in how they look and the man envisions life with them.

Wife number one dresses fashionably and loves to shop. She goes to the market and buys in abundance without much care for her husband’s monthly budget. She cooks elaborate meals with food waste that goes quite literally to the dogs. And moreover, meals in this household are chaotic with five children at the table (this was the average TFR when the commercial was made):

In contrast, wife number two is dressed more plainly and traditionally (with a bindi on her forehead), goes to the store only for what is necessary, grows her own tomatoes, stitches all the children’s clothes and so on. At her table there are only two kids:

Her habits and dispositions mean that the family can afford a bigger house, a better lifestyle and the husband then asks — why not have more children?

To which the woman responds with a firm no, stating that they should instead invest in the two children they already have:

This more elaborate and implicit indication towards family planning was later followed up with a much more famous advert in 1969 titled “Umbrella” [linked]. Again, full color, narrated in English, but simpler and more direct. The premise is straightforward – a man is standing in the rain with his family but is unable to offer all of them protection from the elements, his umbrella is too small and there are too many children (again we see five kids):

What if there were just two children instead? Now everyone is warm, dry, and happy:

See also in the above image the red triangle — this is the symbol for birth control in India and is still used today in all official communication regarding family planning.

Clearly something here worked. My dad is one of five siblings, but me and most of my cousins come in pairs of two.

Moreover, in 1990 the rate of birth control usage was ~36 percent but this has since risen to above 50 percent [52-56% depending on source] in women of reproductive age living with a partner. One caveat here is that many women, especially in rural parts of India, resort to female sterilization as a way of family planning – complete and final. This is often because the onus of contraception falls on the women, which is a separate issue to contend with, but I point it out here because this indicates that increasing the TFR in India has to be a long term campaign. Many families with two kids quite literally cannot have more children. [I have written about this sort of family planning as part of a biographical study on rural India previously (see pages 7-9 of the document linked here if of interest)].

Where does this leave us?

Today Indian’s across the board are all for family planning, for having less children but those who lead more prosperous lives. One only needs to look at the way out falling TFR is being reported in the news and on social-media to see this. Below is a snapshot (from last week) of a front page article in India’s leading English language newspaper, The Times of India. It states that “India has made significant progress in lowering fertility rate, from nearly five children per woman in 1970 to about two, courtesy improved education and access to reproductive healthcare…” – lowering fertility clearly is a positive thing here.

Similarly, the same news on social channels, where the audience tends to be younger, states the following: “Total fertility rate (TFR): India's TFR has fallen to 1.9, below the replacement threshold of 2.1.Long-term outlook: The population is projected to climb to 170 crore before beginning a gradual decline in roughly 40 years. The UN attributes this decline to the increase in educated population, improved reproductive healthcare, and women gaining a voice in the decisions that affect them…” [Source: fayedsouza on instagram]

The comment section of this post was filled with appreciation for how we are solving the over-population problem. The text itself lauds lowering TFR to a more literate, healthier, happier populous where women have more agency. This is a modernized India!

In this paradigm, why should young women in a developing nation even consider having more than two children? We grew up in a culture that prioritized female purity, where we heard stories of stigmatized divorced women and unhappy married ones, of unsupportive husbands and overworked wives, of distant fathers and dependent mothers – why would we surrender ourselves to the same fate? What makes it appealing? Moreover, we would be working against half a century of social conditioning where smaller families symbolized modernization and a more liberal atmosphere for women.

If pro-natalist policy-makers want to shift the tides, especially in India, then they must make larger families more aesthetically appealing to women. Make it a part of happy, new India instead of a cold and calculated economic problem to solve. There are many issues and debates I have not touched upon and this is by no means an all encompassing solution but it cannot hurt to have more empathy for the demographic in question.

With thanks to Stuti Iyer, Mahi Patel, and Harsh Aditya for feedback on drafts.

I don’t know if it’s happening in large enough numbers to affect TFR but poor rural women working in agriculture (e.g., sugarcane harvesting) are opting for or forced into getting hysterectomies to avoid taking days off during their periods.