A Brief History of Painkillers

On the arduous road to making pain a choice

The first time I bought some ibuprofen I was surprised to walk out with a bottle of a hundred pills, it was the smallest quantity available. In contrast, my home country of India lets individuals procure as little as a single tablet at a time. I make this comparison between both ends of the spectrum to highlight that regardless of how the NSAIDs are packaged, their cheap and ubiquitous availability points to the same conclusion – pain has truly become optional for everyone. In fact, a study from 2002 estimated that we consume “40,000 metric tons of aspirin, equating to about 120 billion aspirin tablets [at 300mg a pill].” This number has almost certainly grown and is a shallow reflection of the 131 billion dollar market size that these drugs capture as of last year. [1] [2]

Today we benefit from a remarkable piece of technology that has improved both human productivity and quality of life. Yet, this was not always the case. Strikingly, right up to the turn of the 20th century our tools for dealing with pain were limited and our understanding of the underlying mechanisms even more so – the path to making pain a choice was a long one. Over the centuries, we have fermented poppy plants into opium, shaved willow bark into tonics, and inhaled strange vapors in front of large audiences. Now, a new generation of biotech companies wants to isolate the very “switches” in our nerves and flip them off. Here is a short history of how we got here:

Graph inspired by Saloni Dattani’s excellent article on the Golden Age of Antibiotics.

Opium and Willow Bark in Antiquity

The opium poppy, or the “joy plant” as the Sumerians called it, emerged as one of the first breakthroughs when discovered in the Fertile Crescent. By the time of the Egyptian empire, opium had become a staple remedy. Its ability to induce sleep and numb suffering was so pronounced that doctors attributed its powers to gods and goddesses, gradually weaving opium into Egyptian mythology. [3]

In the Greco-Roman world, the poppy plant featured prominently in literary tradition, with both Homer and Virgil drawing connections between opium-induced sleep and death. In Virgil's Aeneid (IX, 433-37) [4], for example, he writes of the one whose “neck droops: limp as a crimson flower…frail as poppies, their necks weary, bending.” Hippocrates too reportedly used opium along with white willow bark, which he recommended for fevers and aches. This willow bark is particularly significant as it contains a precursor to aspirin’s active ingredient, acetylsalicylic acid.

These ancient remedies, however effective, carried major burdens. Opium easily triggered dependence; prominent historical figures, such as Marcus Aurelius, reportedly consumed daily doses [5]. For centuries, civilizations accepted this trade-off because better options simply didn't exist. When sedation was needed – even for procedures as basic as tooth extraction or treating battlefield wounds – opium remained humanity’s best offering.

Chloroform, Ether, and the Birth of Modern Anesthesia

I want to take a short detour here to talk about anesthesia because while opium relieved certain aches or helped patients doze through lesser procedures, the agonies of major surgery remained horrifying until the mid-19th century. Surgeons worked as quickly as possible while assistants restrained the writhing patient. Speed was prized: the best “sawbones” performed amputations in mere minutes [6]. The notion that we could completely extinguish pain and any memory of it by rendering someone unconscious was, for most, inconceivable.

That changed in 1846, when a Boston dentist, William Morton, demonstrated the use of Ether for a tumor removal in what became known as the “Ether Dome” demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital. Journalists and doctors were astonished: the patient lay still, felt no pain, and awoke unaware of the knife. Soon after, a Scottish obstetrician, James Young Simpson, began experimenting with Chloroform, testing the sweet smelling liquid on his friend in his dining room. While today it is most commonly associated with a mysterious white handkerchief in works of crime fiction, for many decades it was the go-to method of inducing unconsciousness. [7] [8]

However, intriguingly it was not widely accepted at first. The public was scandalized and some religious authorities condemned the effort to abolish pain in childbirth as meddling with the natural order. But the tide turned definitively in 1853, when Queen Victoria used chloroform for the birth of her eighth child. Knowing that it was good enough for the monarch, put most moral objections to bed and almost overnight anesthesia gained broad acceptance in Britain. [9]

Chloroform did have risks though. It came with a narrower safety margin than ether and an overdose could cause sudden cardiac arrest, claiming a patient’s life within minutes. Over time, anesthetists refined dosages, and the presence of a specialized “anesthesiologist” gradually became standard in operating rooms. For the first time, surgeries could be performed meticulously which helped continue the rising trend of a professionalized medical class.

Morphine, Heroin, and the Rise of Modern Opioids

While anesthesia was part of the medical puzzle, for most everyday uses opium still ruled, but it was the isolation of morphine in the early 1805 that launched a true pharmacological revolution. German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner extracted potent crystals from raw opium resin and named them “morphium,” referencing Morpheus, the Greek god of sleep and dreams. Morphine quickly found its way into doctors’ kits: it was stronger than opium’s crude preparations, easier to measure, and when injected, provided rapid, dramatic relief [10]. Around the same time, the hypodermic syringe was perfected (1844-1851). Combined, morphine plus the syringe offered near-instant sedation of severe pain – an appealing prospect, especially in warfare. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), tens of thousands of soldiers received morphine injections for gunshot wounds or amputations. Although they recovered physically, many returned home with a new affliction: morphine dependence, or what was labeled “the soldier’s disease.”[11]

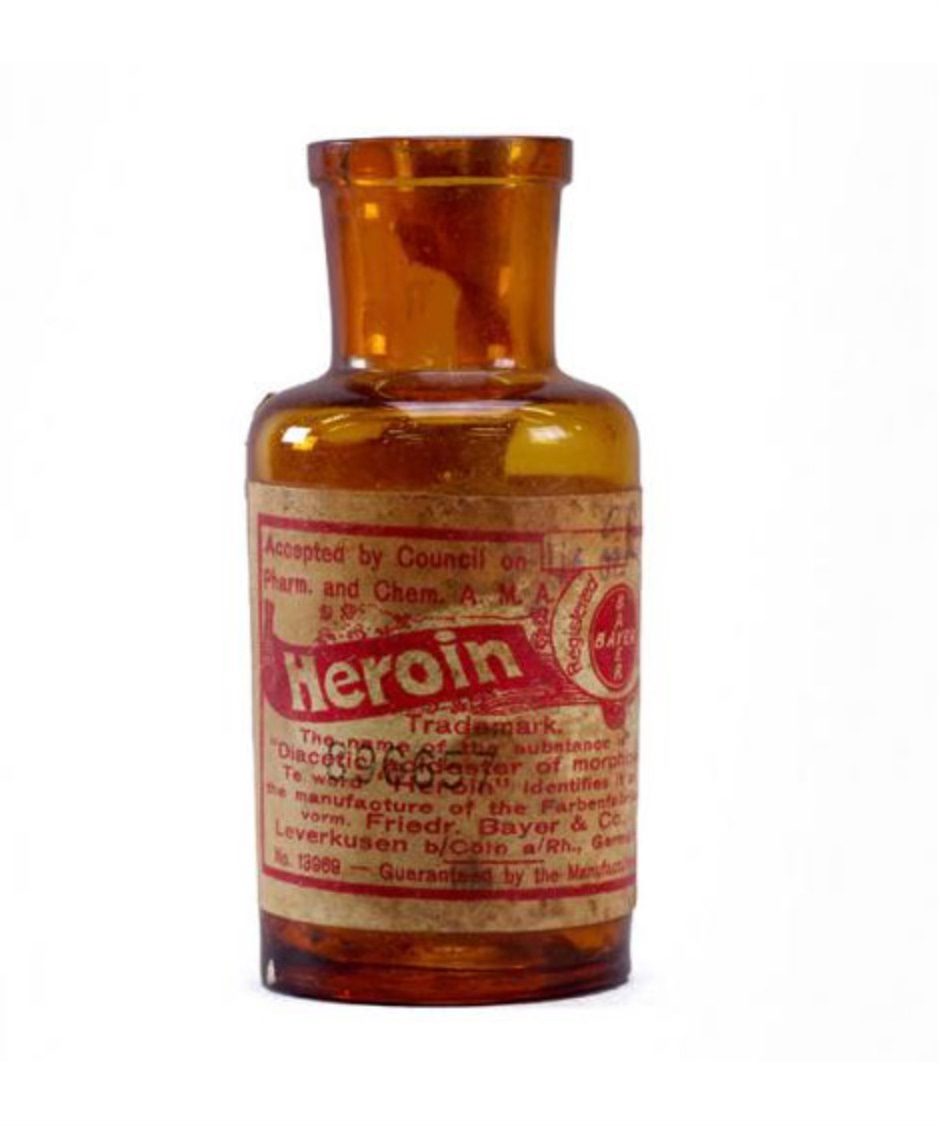

This kickstarted the quest to find an “even safer, less addictive” form of morphine led to more chemical feats: diacetylmorphine (later dubbed heroin), hydrocodone, oxycodone, and so on. Each debuted with optimism within a rather lax regulatory environment. Heroin, for instance, was sold by Bayer in the late 1890s as a fix-all cough remedy.

By the 20th century, opioids had branched into countless variants, from the moderate (like codeine) to the terrifyingly strong (like fentanyl). The analgesic power was never in doubt, making them indispensable for severe acute pain or end-of-life care, but so was their capacity to create a vicious cycle of addiction.

Aspirin, NSAIDs, and Over-the-Counter Relief

Despite opium’s saga, a more humble contender was waiting in the wings for simpler pains: derivatives of the willow bark. Moreover, while Bayer & Co. might have misstepped with heroin, Felix Hoffmann, a scientist at the company developed acetylsalicylic acid, soon marketed as Aspirin (1899). Compared to opiates, aspirin had fewer addictive properties and was particularly good at reducing inflammation and fever.

Aspirin caught on at a scale rarely seen before in medicine and started something of a revolution in the class known collectively as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ibuprofen, introduced in the 1960s, claimed to be gentler on the stomach lining. Naproxen, diclofenac, and others soon followed. Collectively, these “over-the-counter” analgesics became a staple of everyday life, providing relief from headaches, muscle sprains, period pains, minor arthritis flare-ups and everything in between. [12]

Yet, most would soon be dethroned by a much earlier discovery – paracetamol. It lacks the anti-inflammatory label its counterparts boast but generally outsells them because it spares the stomach. While it is the go-to treatment for fevers and aches in all age groups, it is also the leading cause of acute liver failure and responsible for “more than 100,000 calls to Poison Control Centers, 56,000 emergency room visits, 2,600 hospitalizations and nearly 500 deaths” in the United States. [13] [14]

Where does this leave us? Opium and its derivatives are addictive, NSAIDs can cause gastrointestinal bleeding or kidney strain at high doses, and acetaminophen can destroy the liver.

Nav1.7 (and Nav1.8) Inhibitors

The recent approval of Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ Suzetrigine (VX-548), marketed under the brand name Journavx, marks the beginning of what could become the next major chapter in analgesia. Unlike previous drug classes, Suzetrigine targets the Nav1.8 sodium channels to silence pain directly at its source in peripheral nerves, circumventing the brain’s reward circuits entirely.

The inspiration for this approach came from a rare genetic anomaly known as Congenital Insensitivity to Pain (CIP), where individuals lack functional Nav1.7 sodium channels, rendering them completely unable to sense pain. The idea was that if scientists could block this specific channel pharmacologically then they might be able to replicate this “pain-free” state without the addictive and sedative consequences of opioids. However, early clinical trials of Nav1.7 inhibitors produced mixed results, revealing that targeting just that channel was insufficient in reliably extinguishing pain – it turns out that the bodies of individuals with CIP also compensate by producing heightened levels of natural opioids (like endorphins and enkephalins). [15]

Vertex Pharmaceuticals then shifted focus slightly, concentrating on Nav1.8 which is a closely related channel that also transmits signals for inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Their new compound, VX-150 demonstrated notable efficacy in early human trials, paving the way for their next-generation molecule, VX-548 (Suzetrigine). Clinical studies from 2022 onwards confirmed VX-548’s effectiveness, showing significant pain relief following surgeries like bunionectomy and abdominoplasty, rivaling opioid analgesics without the same side effects. [16]

In general but also in context of the story so far, the FDA’s 2025 approval of Suzetrigine thus represents a landmark moment. It introduces the first non-opioid oral analgesic class in decades, capable of substantial acute pain relief with minimal adverse effects – no respiratory depression, no sedation comparable to opioids, and crucially, no addiction risk.

Challenges remain however, with Phase-3 trials of Biogen’s Nav1.7 inhibitor, vixotrigine, withdrawn after mixed results during Phase 2. Despite these setbacks, Vertex’s breakthrough with Nav1.8 inhibition represents a necessary step forward; perhaps overcoming pain is within our scientific reach. While history has repeatedly shown that pain relief is rarely simple, we might just be able to make pain a thing of the past for everyone. [17]

References:

Fascinating piece, thanks for sharing 👍